It’s always in the sky. Countries and businesses around the world are eyeing it with economic hopes and dreams. It’s the moon. But what is it, anyway? How far is the moon from Earth? And is there really water up there?

Here’s everything you could possibly want to know about the moon.

🌓 How Did the Moon Form?

The moon is Earth’s only natural satellite, though we’ve recently picked up an unnatural satellite, as well. Scientists think the unnatural satellite, made by humans, is the remains of a rocket from a failed mission to the moon in 1966.

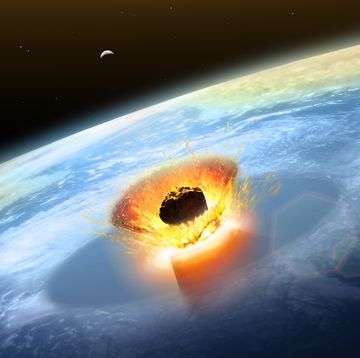

The most commonly held theory for the moon’s creation is known as the “Giant Impact Hypothesis.” It states that a young planet the size of Mars, named Theia, crashed directly into Earth, and the resulting impact formed the moon.

However, there have long been questions about this theory, like what happened to Theia afterward? Is the moon composed of a mixture of materials from Earth and Theia? A NASA study from 2019, for instance, cast doubt on the Giant Impact Theory. Specifically, scientists couldn’t find enough of a large group of Earth elements in the moon, even though the moon should contain them, per the Giant Impact Theory.

Yet in 2020, a NASA-led team examined lunar samples that Apollo astronauts brought back to Earth more than 50 years ago. Planetary scientists know that the element chlorine vaporizes at low temperatures, so they use chlorine to track planet formation. The scientists found evidence that the moon rocks contained more of the heavy chlorine isotope, while Earth has more light chlorine. The researchers theorized that as Earth and the moon reformed after the impact, the moon lost most of its light chlorine, because the larger of the two, Earth, drew it away; this supports the Giant Impact Theory. “The chlorine loss from the moon likely happened during a high-energy and heat event, which points to the Giant Impact theory,” Tony Gargano, one of the lead researchers, said in a NASA press release at the time.

The truth is, humanity’s understanding of lunar geology is limited. But there are many things that various astronauts have learned from the instruments they’ve left behind. For one, we’ve learned that the moon has a small, metallic core comprised of nickel and iron. Like Earth, it is a differentiated world, meaning it has various layers with different compositions. Beyond the core, there’s a mantle and a crust.

“Interestingly,” NASA reports in its online FAQ about the moon, “the crust of the moon seems to be thinner on the side of the moon facing Earth, and thicker on the side facing away. Researchers are still working to determine why this might be.”

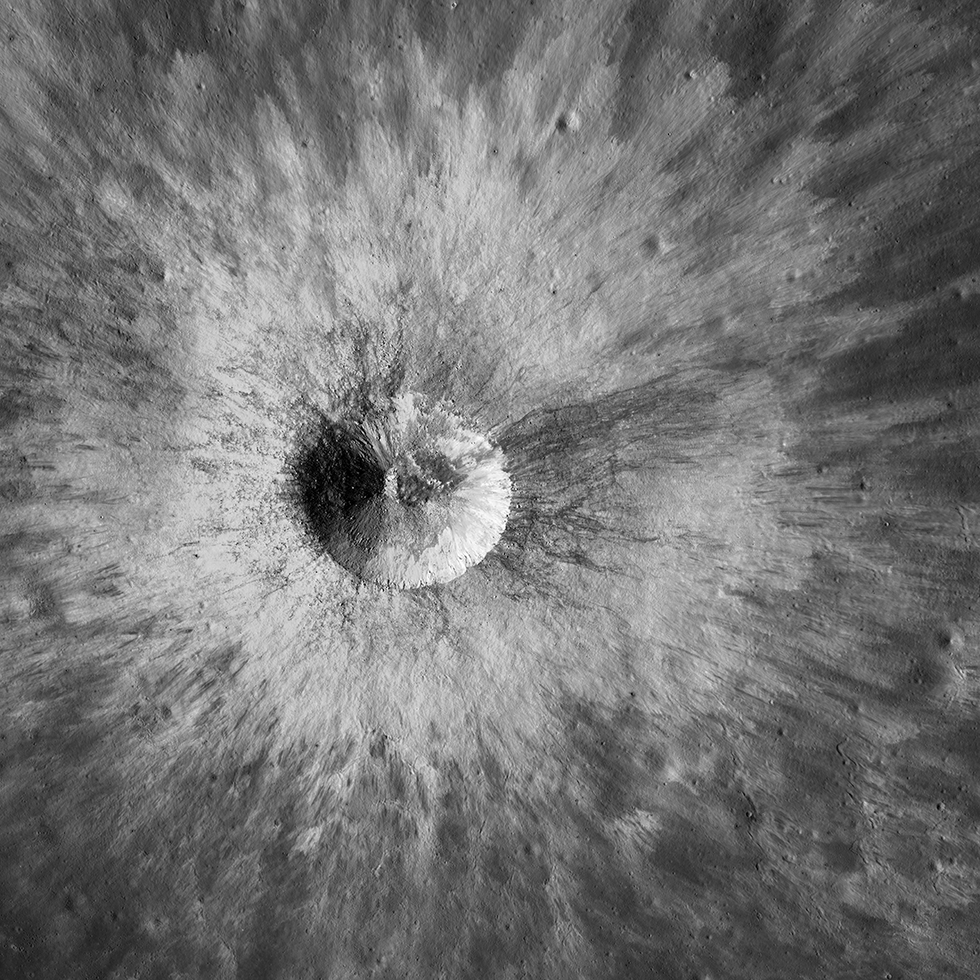

But on a surface level, it’s very clear what the moon is: gray, dusty, and lifeless. There once was likely volcanic activity on the moon while it was young, three or four billion years ago, but that time has long since passed. Beyond the occasional moonquake, not much happens amidst the impact basins that were once brimming with lava. Scientists aren’t sure what causes some of the “shallow” moonquakes, but they can register a whopping 5.5 on the Richter scale. Some “deep” moonquakes are caused by vibrations from meteorite impacts, and others are caused by sudden warming and expansion of the frozen crust when it faces the sun after two weeks of night.

There are impact craters and beautiful lunar swirls, but beyond the physical landmarks on the moon, there’s nothing but dust—a lot of dust.

However, after speculating about the possibility of water on the moon since the late 2000s, scientists have finally proven it. NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) confirmed the presence of H2O on a sunlit region of the moon in 2019. Previous observations of molecules in lunar mineral samples indicated either water (H2O) or a closely related chemical compound called Hydroxyl (OH).

The total volume of water found was only about 12 ounces, spread thinly across one cubic meter of surface soil. Still, it’s a mystery why there is any water at all on this gray desert, and why it hasn’t evaporated. Scientists speculate that the water may be a byproduct of meteorite impacts containing H2O, but that’s only one possible solution.

🌓 How Long Does It Take the Moon to Orbit Earth?

It takes a little over 27 days—27.322, to be exact. Coincidentally, it also takes the moon 27 days to rotate on its own axis. That’s what scientists call “synchronous rotation,” and it’s why the moon appears to be still when it’s in the night sky.

The moon’s orbit of Earth follows what scientists call an elliptical path, shaped more like an oval than a circle. So while we can’t see the moon spinning, we can see it change in size. It’s just a matter of perspective, but it reflects how the moon interacts with Earth. When the moon is farthest away from Earth, scientists refer to that as the “apogee,” and when it is closest, it’s at its “perigee.”

🌓 How Far Away Is the Moon From Earth?

The moon’s distance varies within its orbit. At its apogee, it’s 252,088 miles (405,696 kilometers) from Earth. At its perigee, it’s closer, at 225,623 miles (363,104 kilometers). That works out to an average of 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers). That’s around 60 times the radius of Earth, or enough distance for 30 Earths in between.

But many scientists suspect the moon was once far closer to Earth. Simulations suggest that during its formation, the moon’s distance from the planet was only three to five times the radius of Earth. That translates to anywhere between 20,000–30,000 kilometers away.

🌓 How Does the Moon Affect the Tides?

Beyond looking lovely in the night sky, perhaps the way the moon most directly affects Earth is through its influence on the planet’s oceans. Just like Earth’s gravitational pull keeps the moon tethered to the planet, the moon’s own gravitational pull has an effect on Earth.

Of course, these two gravitational pulls are hardly equal. The moon has only 1/100th the mass of Earth, making for much weaker gravity. But in the scope of interplanetary physics, the two bodies are quite close. So that gives the moon enough power to affect the planet in a small way, and water moves much easier than land does. Thus, the moon creates what scientists call a “bulge,” or a movement of water.

As the moon rotates around Earth, the water facing the moon always wants to move toward it, a phenomenon known as “high tide.” However, a bulge also forms on the side of the planet facing away from the moon, so that’s why in a full 24-hour span, we experience two high tides and two low tides.

The powerful gravity of the sun also affects tides, especially when the three bodies involved are all in alignment. When Earth, the sun, and the moon cosmically align, the tides become stronger, bulging out of the ocean more. These are known as “spring tides,” which have nothing to do with the season. Rather, it’s meant to describe how the tides spring forth from the ocean. They usually occur twice a year.

And there are after-effects. A full week after spring tides, the sun and moon find themselves at right angles. As a result, the moon partially cancels out the gravitational pull of the sun, resulting in high tides being a little lower and low tides being a little higher. These are known as “neap tides.”

🌓 What’s the Dark Side of the Moon?

A classic rock album by Pink Floyd.

But seriously, there’s no actual dark side of the moon, because the moon rotates just like Earth; as the moon rotates around Earth, it also rotates around the sun. This hidden region is better known as “the far side of the moon.” While it has presented a challenge for explorers for decades, China recently became the first country in history to land an object on the far side of the moon.

And scientists are learning more and more about our planetary neighbor’s far side every year. For example, scientists recently unlocked a lunar mystery that has puzzled them for decades: Why does the far side of the moon have fewer volcanic craters than the near side? It turns out that decaying radioactive elements, like potassium and thorium, are to blame. (The near side is chock full of them.)

🌓 Why Does Earth Always See the Same Side of the Moon?

There’s a lot of symmetry between the moon and Earth, most commonly seen in a phenomenon known as “tidal locking.” That means that the moon’s orbital period is equal to its rotational period. At the same time it’s orbiting Earth, it’s rotating. Earth has been stuck with the synchronous side for billions of years.

So throughout all of that time, humanity has had a chance to become very familiar with the crater-filled side it sees, perhaps leading it to anthropomorphize a man on the moon.

🌓 Will We Always Have a Moon?

Not when the sun becomes a red dwarf in billions of years. Red dwarfs are small, dim stars that burn through their fuel very slowly. Both Earth and its satellite will likely be incinerated when the sun enters its next stage of life—but things will get weird before that, too.

“After billions of years (the precise number is hard to estimate), the moon will get to its final end state where it orbits more slowly and Earth spins exactly as fast as the moon orbits. One side of Earth will see the moon fully up in the sky while the other side of Earth will never see the moon,” according to Everett Schlawin of Cornell University on its website, Ask an Astronomer.

Imagine: On one side of the planet, a permanent moon will fill the sky, while the other side of the planet gets a night sky full of stars. If the sun wasn’t going to destroy everything very soon after that, it’d be worth seeing.

..David Grossman is a staff writer for PopularMechanics.com. He's previously written for The Verge, Rolling Stone, The New Republic and several other publications. He's based out of Brooklyn.