A Timothy Leary for the Viral Video Age

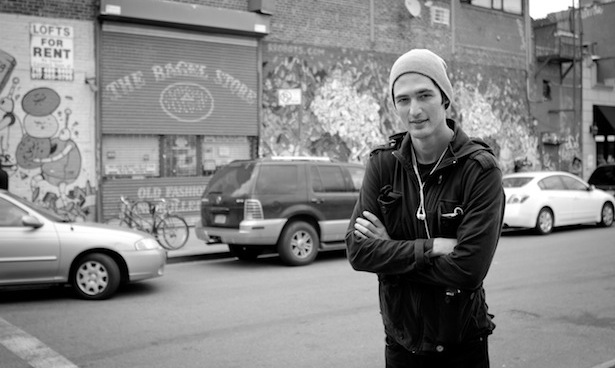

Meet Jason Silva, the fast-talking, media-savvy "performance philosopher" who wants you to love the ecstatic future of your mind.

Meet Jason Silva, the fast-talking, media-savvy "performance philosopher" who wants you to love the ecstatic future of your mind.

I want to introduce you to Jason Silva, but first I want you to watch this short video that he made. It will only take two minutes, and watching it will give you a good idea if it's worth your time to read the extensive interview that follows:

If you ever wondered what would happen if a young Timothy Leary was wormholed into 2012, complete with a film degree and a Vimeo account, you have your answer: Jason Silva. If Silva, who was born in Venezuela, seems to have natural screen presence, it's because he's no stranger to media; he worked for six years as a host at Current TV before leaving the network last year to become a part-time filmmaker and full-time walking, talking TEDTalk.

Like Leary, Silva is an unabashed optimist; he sees humankind as a species on the brink of technology-enabled transcendence. Silva is an avid evangelist for the technological singularity---the idea that technology will soon bring about a greater-than-human intelligence. It's an idea that Ray Kurzweil has worked hard to popularize in tech circles, but Silva wants to push it out into the mainstream, and he wants to do it with the slickest, most efficient idea vehicle of our time: the viral video. He has spent the last three years making (really) short films that play like movie trailers for ideas; he compares them to shots of "philosophical espresso."

Silva's work is starting to get some traction; his short films have been viewed over half a millon times, and in just the past year he has been invited to speak at Google, the Singularity Summit, and The Economist's Ideas Festival. Talking to him it's easy to see why. He has a singular conversational style, marked by a virtuosic ability to quote his favorite thinkers verbatim, and a rhetorical endurance that allows him to riff long and deep on an impressive range of topics. What follows is my wide-ranging conversation with Silva about his films, the human condition, and the promise of technology.

I've heard you described in a lot of interesting ways, as a performance philosopher, an Idea DJ, or even as a shaman---What do those terms mean to you and is there anyone else out there that you see as performing a similar cultural role? Are there historical precedents for what you're trying to do?

Silva: Definitely. I first heard this term "performance philosophy" on a website called Space Collective that was started by the Dutch filmmaker Rene Daalder as a way for humans to imagine what it might be like to eventually leave the Earth. I was reading an article about Timothy Leary that said that Timothy Leary and Buckminster Fuller used to refer to themselves as "performance philosophers," and that really stuck with me.

When Timothy Leary was in prison he was visited by Marshall McLuhan, who told Leary "you can't stay way out on the fringes if you want to compete in the marketplace of ideas---if your ideas are going to resonate, you need to refine your packaging." And so they taught Leary to smile, and they taught him about charisma and aesthetic packaging, and ultimately Leary came to appreciate the power of media packaging for his work. According to the article, this is where Timothy Leary the performance philosopher was born, and when he came out of jail all of the sudden he was on all these talk shows, and he was waxing philosophical about virtual reality, and downloading our minds, and moving into cyberspace. All of these ideas became associated with this extremely charismatic guy who was considered equal parts rock star, poet and guru scientist---and that to me suggests the true power of media communications, because these guys were able to take these intergalactic sized ideas and spread them with the tools of media.

The problem, as I see it, is that a lot of these stunning philosophical ideas are diluted by their academic packaging; the academics don't think so because this is their universe, they could care less about how these ideas get packaged because they're so enmeshed in them. But the rest of us need another way in. We need to be told why these ideas matter, and one of the ways to do that is to present them with these media tools.

When I heard the term "performance philosophy," it really resonated, because I went to school in film and philosophy, those were my two majors. I always loved watching movies because I loved what certain moments inside of films did to me. Movies have these transcendent moments where everything is just right, from the dialogue to the music to the lighting, to the narrative context; everything is just perfect and something magical happens---the film breaks through the screen and does something to you. And so those moments were what I wanted to create, and it just so happened that my craft has always been speaking. There has always been this narrator in me---I loved ideas, and part of the great love affair I would have with ideas consisted of talking about them. Talking about an idea was like having sex with it.

I used to host these salons at my house when I was growing up, and I would be very intentional about the aesthetics. I would create a beautiful space and I would handpick the people that were invited; we were kind of inspired by Charles Baudelaire's 'Hashish House,' where these guys would get together and drink wine and smoke hashish and talk about ideas. And we used to film it; I have video of myself as a 16 year old going ecstatic over these ideas, and even then I knew that these ecstatic visions we were having, these ecstatic moments, were worth memorializing. So I had this combo, this obsession with documentation, which I didn't accomplish with the pen, but rather with the video camera, and the love of using words to articulate feeling. That combo had already formed, and it's what eventually brought me to Current TV, and you can see it today in the videos I've been making since I left Current.

And these videos that you're making now? How would you describe them?

Silva: I see them as souvenirs that I'm bringing back with me from the ecstatic state. Some people have criticized me for being overly expository, they see me as the equivalent of a voice-over narrator in a film who's telling you what's happening on a screen even though you can see it right in front of you. But it's not enough to feel the experience; it needs to be narrated in real time. That method really works for me because narrating my experience creates a self-amplifying feedback loop whereby articulating experience allows me to feel it in a richer way, which in turn helps me articulate it in a richer way, and so on. That feedback loop helps you sort of author your way into your experience, like writing your name on a tree and saying "Jason was here." It's a way of saying "I experienced something and it matters," a way of throwing an anchor into something that's ephemeral and trying to hold it in stasis. That's what we do with all of our art. A beautiful cathedral, a beautiful painting, a beautiful song---all of those are ecstatic visions held in stasis; in some sense the artist is saying "here is a glimpse I had of something ephemeral and fleeting and magical, and I'm doing my best to instantiate that into stone, into paint, into stasis." And that's what human beings have always done, we try to capture these experiences before they go dim, we try to make sure that what we glimpse doesn't fade away before we get hungry or sleepy later.

And we're hoping that at some point we can get rid of the hungry and sleepy problem.

Silva: Exactly, because that's really the point, right? We want to transcend our biological limitations. We don't want biology or entropy to interrupt the ecstasy of consciousness. Consciousness, when it's unburdened by the body, is something that's ecstatic; we use the mind to watch the mind, and that's the meta-nature of our consciousness, we know that we know that we know, and that's such a delicious feeling, but when it's unburdened by biology and entropy it becomes more than delicious; it becomes magical. I mean, think of the unburdening of the ego that takes place when we watch a film; we sit in a dark room, it's sort of a modern church, we turn out the lights and an illumination beams out from behind us creating these ecstatic visions. We lose ourselves in the story, we experience a genuine catharsis, the virtual becomes real---it's total transcendence, right?

Right.

Silva: But then think of being in the movie theater and you have to pee, or you have a headache, or you ate too much for lunch before the movie and you're being weighed down by your metabolism. This is biology getting in the way of the potential that consciousness has to experience these heightened states. So you have this interesting thing happening where biology is this emergent phenomenon that builds upon its own complexity, and it leads to the emergence of consciousness, but then consciousness wants to free itself from constraints that biology sets forth. So even though biology causes consciousness, it also burdens it.

So far you've been focusing on these compressed two minute videos, "philosophical espresso," as you call them, but I also understand that you're working on a feature length film called "Turning Into Gods."

Silva: The "Turning Into Gods" project really grew out of this twelve minute documentary called The Immortalists that I did when I was still at Current, when I was first thinking about the singularity and immortality and all that, and I figured out "hey, wait a minute, I work for a media company---I can get access to these guys!" and that's when I first connected with Ray Kurzweil. I went to visit him at his office in Massachusetts, and I took a camera crew along with me. I interviewed Kurzweil and then these guys called "The Immortalists" who believe we're going to transcend biological aging and mortality, and I put together this kind of gonzo style documentary that ended up not running on Current because they thought it was too esoteric, because it was basically just me having these conversations with these guys about transcending mortality. Philosophical questions, mainly; I didn't want to know the science of it as much as I wanted to know why it was okay for us to do, and what about the people who say it's playing with nature, and that sort of thing. I was trying to find my own justifications as echoed through their voices.

I ended up putting it on YouTube and it got all this great buzz online. I was sitting there at Current and I'd been there a few years and I wasn't feeling as creatively fulfilled, because I felt as though I was being molded into more of the typical television personality when really I just wanted to be myself. So as a sort of passion project on the side, I started remixing the unused footage from the film, and I cut into what I called a "mood reel" or a concept trailer for a longer film. The idea was to revisit "The Immortalists" and turn it into a longer project, and that's where "Turning Into Gods" came from. The idea came from a book by the thinker Alan Harrington where he says, "after creating the gods, we are turning into them." And to me that's interesting, this idea of gods as blueprints, these imaginary omniscient deities we worship, we're going to turn into them. We invented them, and so it follows that our ideas of gods are great virtual models, great outlines for what we want to become. Alan Harrington has this other great quote where he says "we must never forget, we are cosmic revolutionaries, not stooges conscripted to advance a natural order that kills everyone." He didn't have this cosmic inferiority complex that you see afflicting so much of mankind---he's like no, we're going to build the Tower of Babel and we are. Cavemen ended up flying to the moon, and when you think about that, it's not exactly bold to say that we might transcend biology and entropy.

When did you first come across the idea of the singularity, this notion that at some point in the future technology is going to accelerate so quickly that the human experience will become unfathomable to humans now?

Silva: I think it was around 2004 or 2005. I've always been somebody who goes into rabbit holes with philosophical ideas. I used to create these journals in high school that were compilations of articles about things I was interested in, like the health benefits of marijuana, the health benefits of drinking---I was always interested in the ways artists used intoxicants to achieve creativity, and the thing I kept hitting on was the necessity of departing from the ordinary in order to see things anew. This sense that we had to remove ourselves from our reality tunnels, and strip away our preconceptions by any means necessary, whether that's through meditation, yoga or whatever. I've always been fascinated by the short cut that marijuana, or even alcohol, offered people like Charles Baudelaire or Freud---this strange ability we have to shake ourselves out of context in these a la carte ways.

This journal had chapters on the human condition, and even on romance, where I would collect random little poems and articles that contained little sentences that I though described the subjective experience of romantic love really well, or the pain of the passing of time really well. I was always really moved by this film Before Sunrise, with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, which is this exquisite rendering of what it feels like to fall in love when you're out of context, when you're not in your home city, not in your hometown, but somewhere else where nobody knows your name. You're walking around the cities of Europe contrasting the ancient past with the present, and you're losing yourself in an intimate moment, falling in love, you have this longing and yearning, and then the knot in your stomach that tells you "oh no, we're back in real time and this magical moment is going to be over."

This haunting idea of the passing of time, of the slipping away of the treasured moments of our lives, became a catalyst for my thinking a lot about mortality. This sense that the moment is going to end, the night will be over, and that we're all on this moving walkway headed towards death; I wanted a diversion from that reality. In Ernest Becker's book The Denial of Death, he talks about how the neurotic human condition is not a product of our sexual repression, but rather our repression in the face of death anxiety. We have this urgent knot in our stomach because we're keenly aware that we're mortal, and so we try to find these diversions so that we don't think about it---and these have manifested into the religious impulse, the romantic impulse, and the creative impulse.

As we increasingly become sophisticated, cosmopolitan people, the religious impulse is less relevant. The romantic impulse has served us well, particularly in popular culture, because that's the impulse that allows us to turn our lovers into deities; we say things like "she's like salvation, she's like the wind," and we end up worshipping our lovers. We invest in this notion that to be loved by someone is to be saved by someone. But ultimately no relationship can bear the burden of godhood; our lovers reveal their clay feet and their frailties and they come back down to the world of biology and entropy.

So then we look for salvation in the creative impulse, this drive to create transcendent art, or to participate in aesthetic arrest. We make beautiful architecture, or beautiful films that transport us to this lair where we're like gods outside of time. But it's still temporal. The arts do achieve that effect, I think, and so do technologies to the extent that they're extensions of the human mind, extensions of our human longing. In a way, that is the first pathway to being immortal gods. Particularly with technologies like the space shuttle, which make us into gods in the sense that they let us hover over the earth looking down on it. But then we're not gods, because we still age and we die.

But even if you see the singularity only as a metaphor, you have to admit it's a pretty wonderful metaphor, because human nature, if nothing else, consists of this desire to transcend our boundaries---the entire history of man from hunter gatherer to technologist to astronaut is this story of expanding and transcending our boundaries using our tools. And so whether the metaphor works for you or not, that's a wonderful way to live your life, to wake up every day and say, "even if I am going to die I am going to transcend my human limitations." And then if you make it literal, if you drop this pretense that it's a metaphor, you notice that we actually have doubled our lifespan, we really have improved the quality of life across the world, we really have created magical devices that allow us to send our thoughts across space at nearly the speed of light. We really are on the cusp of reprogramming our biology like we program computers.

All of the sudden this metaphor of the singularity spills over into the realm of the possible, and it makes it that much more intoxicating; it's like going from two dimensions to three dimensions, or black and white to color. It just keeps going and going, and it never seems to hit the wall that other ideas hit, where you have to stop and say to yourself "stop dreaming." Here you can just kind of keep dreaming, you can keep making these extrapolations of Moore's Law, and say "yeah, we went from building-sized supercomputers to the iPhone, and in forty-five years it will be the size of a blood cell." That's happening, and there's no reason to think it's going to stop.

Going through your videos, I noticed that one vision of the singularity that you keep returning to is this idea of "substrate-independent minds." Can you explain what a substrate independent mind is, and why it makes for such a compelling vision of the future?

Silva: That has to do with what's called STEM compression, which is this notion that all technologies become compressed in terms of space, time, energy and matter (STEM) as they evolve. Our brain is a great example of this; it's got this dizzying level of complexity for such a small space, but the brain isn't optimal. The optimal scenario would be to have brain-level complexity, or even higher-level complexity in something that's the size of cell. If we radically upgrade our bodies with biotech, we might find that in addition to augmenting our biological capabilities, we're also going to be replacing more of our biology with non-biological components, so that things are backed up and decentralized and not subject to entropy. More and more of the data processing that makes up our consciousness is going to be non-biological, and eventually we might be able to discard biology altogether, because we'll have finally invented a computational substrate that supports the human mind.

At that point, if we're doing computing at the nano scale, or the femto scale, which is even smaller, you could see extraordinary things. What if we could store all of the computing capacity of the world's computer networks in something that operates at the femto scale? What if we could have thinking, dreaming, conscious minds operating at the femto scale? That would be a substrate independent mind.

You can even go beyond that. John Smart has this really interesting idea he calls the Transcension Hypothesis. It's this idea that that all civilizations hit a technological singularity, after which they stop expanding outwards, and instead become subject to STEM compression that pushes them inward into denser and denser computational states until eventually we disappear out of the visible universe, and we enter into a black-hole-like condition. So you've got digital minds exponentially more powerful than the ones we use today, operating in the computational substrate, at the femto scale, and they're compressing further and further into a black hole state, because a black hole is the most efficient computational substrate that physics has ever described. I'm not a physicist, but I have read physicists who say that black holes are the ultimate computers, and that's why the whole STEM compression idea is so interesting, especially with substrate independent minds; minds that can hop back and forth between different organizational structures of matter.

To me one of the interesting ways of thinking about the singularity is to think of it as an "end of history" notion. I actually think it has a lot in common with religion in that respect. What do you say to people who view this idea as simply an updated reselling of the rapture?

Silva: It's a good argument. When you listen to the bullet points of what a technological singularity might offer a civilization---"we won't die!" and "we'll be really happy!" and "we'll be like magical beings!"---it does sound a little bit like the geek version of the rapture. But I always go back to the fact that what we've always done with tools at our disposal is try to craft the greatest of all possible worlds for human flourishing. Religion, for instance, was this psychological technology we used to map and paint and idealize a utopia, and it was a great metaphor but unfortunately people took it too literally. The idea of a rapture was us painting an ideal, we were singing this song about the way we wish that things could be. Heaven is just a metaphor for us saying "wouldn't it be great if," "wouldn't it be great if we didn't lose everybody we love," "wouldn't it be great if we just kept growing and learning instead of withering away and dying." But then it got institutionalized and corrupted and taken too literally. With technology, we've been doing the same thing we used to with religion, which is to dream of a better way to exist, but technology actually gives you real ways to extend your thoughts and your vision.

In one of your films you quote Alan Harrington as saying "The philosophy that accepts death must itself be considered dead, its questions meaningless, its consolations worn out." Do you think that's true? I ask because I'm skeptical, partly because I'm not sure it's the task of philosophy to console, but also because I can imagine philosophies consistent with death that have quite meaningful questions to ask. Besides, even if you kick the can down the road trillions of years, you still have the heat death of the Universe to contend with.

Silva: Oh, you're absolutely right---in the book he's talking about death the way that we normally think of it, corporeal death after seventy or eight years. Harrington's book was an indictment against the philosophy that tells you that suffering is God's will. He's talking about the situation where a child dies after a battle with cancer, and a priest tells a parent "it was God's will" to make them feel better. Any attempts at offering a consoling reason to accept suffering, he says, should be thrown out the window, because those hollow consolations only make us passive in the face of injustice. If somebody's little daughter dies of cancer, that's not fair; the fact that there's people still starving in the world; that's not fair either. And he's saying that if we're ever going to get our act together when it comes to transcending our biological limits, we need do away with the philosophies that teach consolation and acceptance.

And when you think about it, human beings don't practice acceptance. That's why we go to the moon---because we do not accept that we're not supposed to go to the moon. People object and say you're messing with nature, but this dichotomy between nature and technology is the biggest myth of all. Buckminster Fuller used to say, "look at the earth---the biosphere that sprouted the flower is the same biosphere that sprouted the microprocessor." Technology emerged from the biosphere, and it's just as much a part of the technological world as organic matter or plants or whatever. A seed, for instance, is just nanotechnology that works; you plant it and it self-organizes and self-assembles into a tree.

I think that technology is just evolution evolving its own evolvability, to quote Kevin Kelly. He's got this idea that everything is on a continuum, and humans are stuck right in the middle between the stuff that's born and the stuff that's made. We human beings are the eyes and ears of the universe, the thinking stratum of the universe, and in some sense we have become evolution---because of us, evolution can now think.

As a guy who's clearly excited about technology, what technological frontier excites you the most? In my case, it's space---among other things of course---but I'm curious what it is for you.

Silva: I get off on space too, because space allows us to contemplate vastness itself; the canvas that space offers has no borders, and that does interesting things to the mind. The mind is always participating in these feedback loops with the spaces it resides in; whatever is around us is a mirror that we're holding up to ourselves, because everything we're thinking about we're creating a model of in our heads. So when you're in constrained spaces you're having constrained thoughts, and when you're in vast spaces you have vast thoughts. So when you get to sit and contemplate actual outer space, solar systems, and galaxies, and super clusters---think about how much that expands your inner world. That's why we get off on space.

I also get off on synthetic biology, because I love the metaphors that exist between technology and biology: the idea that we may be able to reprogram the operating system, or upgrade the software of our biology. It's a great way to help people understand what's possible with biology, because people already understand the power we have over the digital world---we're like gods in cyberspace, we can make anything come into being. When the software of biology is subject to that very same power, we're going to be able to do those same things in the realm of living things. There's this Freeman Dyson line that I have quoted a million times in my videos, to the point where people are actually calling me out about it, but the reason I keep coming back to it is that it's so emblematic of my awe in thinking about this stuff---he says that "in the future, a new generation of artists will be writing genomes as fluently as Blake and Byron wrote verses." It's a really well placed analogy, because the alphabet is a technology; you can use it to engender alphabetic rapture with literature and poetry. Guys like Shakespeare and Blake and Byron were technologists who used the alphabet to engineer wonderful things in the world. With biology, new generations of artists will be able to perform the same miracles that Shakespeare and those guys did with words, only they'll be doing it with genes.

You romanticize technology in some really interesting ways; in one of your videos you say that if you could watch the last century in time lapse you would see ideas spilling out of the human mind and into the physical universe. Do you expect that interface between the mind and the physical to become even more lubricated as time passes? Or are there limits, physical or otherwise, that we're eventually going to run up against?

Silva: It's hard to say, because as our tools become more powerful they shrink the buffer time between our dreams and our creations. Today we still have this huge lag time between thinking and creation. We think of something, and then we have to go get the stuff for it, and then we have to build it---it's not like we can render it at the speed of thought. But eventually it will get to the point where it will be like that scene in Inception where he says that we can create and perceive our world at the same time. Because, again, if you look at human progress in time lapse, it is like that scene in Inception. People thought "airplane, aviation, jet engine" and then those things were in the world. If you look at the assembly line of an airplane in time lapse it actually looks self-organizing; you don't see all of these agencies building it, instead it's just being formed. And when you see the earth as the biosphere, as this huge integrated system, then you see this stuff just forming over time, just popping into existence. There's this process of intention, imagination and instantiation, and the buffer time between each of those steps is getting smaller and smaller.

I've heard you say that "awe is salvation"---can you explain what you mean by that?

Silva: To me existential despair is the feeling of running up against a limit; existential despair is the feeling of giving up, of surrendering, to a negative entity. When I think about someone dying of an incurable disease, it makes everything dissolve into irony; it makes life seem meaningless. One of the best antidotes to that feeling, that feeling of emptiness or meaninglessness, is awe, fully immersive, emotive and intellectual awe. The way you feel when you watch the Hubble IMAX 3D film stoned out of your mind. That moment where you're hitting your arm against the chair, and you're saying "ohmygodohmygodohmygod" letting out this burst of physical energy just to exclaim viscerally this feeling of awe. And I think that is salvation, because ultimately it lets you fall out of time and into something else. You fall right back into time afterwards, but for a moment you fall out of the stream of time, and that's that feeling we go for in all of our art, and our movies, and that's what my work is about.

In your talks and videos you, much like Ray Kurzweil, tend to lean on Moore's Law a lot, on the exponential growth curves that currently operate in information technology. Where else are you seeing curves like that? I ask because I once heard Bruce Sterling make an interesting point about the singularity, the thrust of which was "hey wait a minute, there's no Moore's law for oil pipelines, there's no Moore's law for energy grids, or water systems." It does sometimes seem like a lot of singularity thinking assumes that computing revolutions will revolutionize each and every frontier of technology, and I'm not sure that's the case. What do you think?

Silva: That's an interesting argument, but I think Kurzweil would say that Moore's Law only kicks into gear when technologies become information technologies, and clearly an oil pipeline isn't going to be an information technology. Biology didn't used to be an information technology, but it's now starting to become one, and now with gene sequencing we are starting to see these exponential curves---gene sequencing is developing faster than Moore's Law predicts in terms of how many genes we can sequence in a given amount of time, and the pricing and so forth.

After biotech, the next thing is nanotech---manipulating matter at the level of the atom---and then matter itself becomes an information technology, and at that point it too will be subject to those exponential growth curves. That explanation makes sense to me; he's not claiming that Moore's Law applies unless we're talking about an information technology.

Nick Bostrom, another transhumanist, takes a kind of sobering view of superintelligence, which is ultimately the hoped-for end product of all of those exponential growth curves. He points out that when the dust settles, it might not be us at the helm of these technologies. Does that worry you? Are you confident that humans will always be able to control technology, or at least control it to the degree required not to be eliminated or severely marginalized by it?

Silva: No, not necessarily. But I don't think that humans as we are now are the be-all end-all. Kurzweil has a great line where he says "we keep talking about them, them, them when it comes to artificial intelligence," but that 'them' is going to be us. I don't see it as this exclusively non-biological separateness that's going to make us its slaves. I see it as being something like creating a digital neocortex as an add-on to our biological neocortex.

Right, but that's a scenario where the human is holding hands with the technology as it passes through the singularity. But you can imagine other scenarios where you've got artificial intelligence that you've created in a computer of some sort, and it figures out a way to rapidly accelerate its own intelligence to the point where human beings are chimpanzees by comparison. We might not be able to leap into that world with them.

Silva: Right. I suppose that is not outside the realm of plausibility, but I still don't see that as separate from us. I see it as one big continuum; there's the trees, the squirrels, and then there's us. I don't think the trees are upset that we've become so advanced. If we separate our subjectivity from this whole narrative, we're all part of this integrated system: the Earth, and the Earth is getting more and more networked. The complexity of the information being exchanged among Earth's self-regulating systems is increasing rapidly.

So you're happy saying, "hey we handed those guys the baton, good for us."

Silva: Exactly. And I think if they're truly trillions of times more intelligent than us, they're not going to be less empathetic than us---they're probably going to be more empathetic. For them it might not be that big of deal to give us some big universe to play around in, like an ant farm or something like that. We could already be living in such a world for all we know. But either way, I don't think they're going to tie us down and enslave us and send us to death camps; I don't think they're going to be fascist A.I.'s.

One of the things that interested me about your videos is their pace, which is very quick, and very informationally dense. It's fascinating to watch you revel in a big rush of ideas against the background of these musical crescendos---the combination of the two seems to generate this kind of cognitive cascading effect, which can be very pleasurable to watch. But I do worry that sometimes you may not be giving your audience time to really examine your premises. Philosophy---good philosophy, anyway---is slow for a reason; it requires careful examination of discrete, logically interlocking ideas. I notice you describe yourself as an epiphany addict; do you ever worry that critical thinking might be a casualty of these epiphanies?

Silva: I think that it's a valid point to say that the pace and kinetic nature of the ideas I'm presenting may not give the audience a chance to fully digest what I'm saying, but at the same time I think it's contextual. When we screen these short videos at conferences like Singularity Summit, or at The Economist's World in 2012 Conference, or at Google where I spoke recently, I come on and introduce the videos, and I give them context, and then we do questions afterward, and there's a deep, rich conversation that takes place.

The other context, the context where most people consume these videos, is the web, but the web has forced us to reconsider all of our notions about how content is disseminated. A lot of new media producers are finding that the short form is better, because the majority of people stop watching YouTube videos after two minutes---even the good ones. And so, I can make a twelve minute video, or even a feature length documentary, which I'm doing, but the reality is that over half a million people have watched these two minute videos on Vimeo. And again, at two minutes, the odds of them sitting through the whole thing are much greater than for a feature film. So it's a necessary trade off, and it works to my advantage, because I can get into this ecstatic state for two minutes and make a short film out of it. And even on the web I do try and create context by providing links to articles or to other work that references the ideas I'm discussing, and that gives people the option of hyper linking themselves into a deeper rabbit hole if they want to.

Ross Andersen is a staff writer at The Atlantic.