There is perhaps no better chronicle of the late 80s/early 90s supermodel era than the stark, natural-lit, black-and-white photography of Herb Ritts. With his statuesque shots of Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, and Christy Turlington, Ritts helped to create a glamorous celebrity aesthetic that defined much of the era. And though early-90s grunge put a dent in his ideal of the celebrity superstar, Ritts’s work still maintains a distinct allure, and offers a fascinating reminder of a bygone pop cultural age.

Two exhibitions opening this month, Herb Ritts at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston and Herb Ritts: The Rock Portraits at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum in Cleveland form not only a retrospective of Ritts’s work, but an era in which supermodels, movie stars, and rock stars were presented as almost Olympian figures – in some ways, a return to the old-school Hollywood glamour of the early celebrity era.

Born in Los Angeles in 1952, Ritts became a photographer almost by accident. While on a trip through the California desert with his friend Richard Gere in the late 70s, a flat tire forced them to make an unscheduled stop at a gas station. In order to kill time while the tire was being repaired, Ritts, who’d picked up photography as a hobby while working for his family’s furniture company, staged an impromptu photoshoot with Gere posing behind the car. The results, which were eventually published in several magazines, helped launch Ritts’s career.

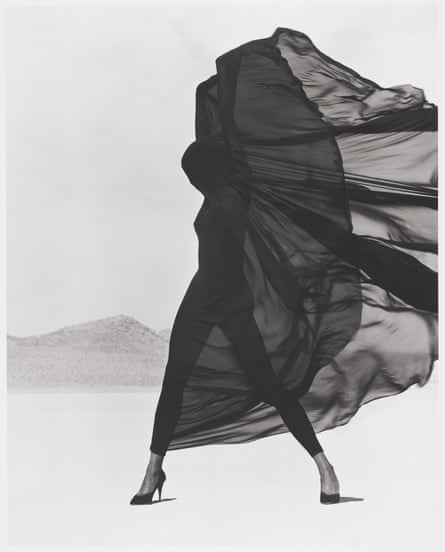

Though photographers like Bruce Weber would influence his early work, by the mid-1980s Ritts would find his own voice, achieved largely through his innate understanding of natural light. He was one of the first commercial photographers to rely on it primarily – specifically the light of California’s “golden hour”, a period roughly between three and six in the afternoon. The effect is a mix of hyperrealism and almost mythic beauty. And while capturing the visual allure of Cindy Crawford or Naomi Campbell was hardly a difficult task, Ritts’s aesthetic also shines through in pictures like Versace Veiled Dress, El Mirage, 1990 and Tony in White, Hollywood, 1988. They show not only Ritts’s classical Greek influences and worship of the human form, but his ability, even without a famous face, to create a feeling of gods among us.

Of course 25 years later, Ritts’s images seem almost quaint. Much of this is due to the emergence of grunge in the early 1990s. It was at the apotheosis of Ritts’s career that Corinne Day’s photo of a 16-year-old Kate Moss graced the cover of the Face magazine in Britain, ushering in the era of drugs, grit and squalor. The old concepts of Amazonian glamour were tossed aside to make way for a new aesthetic that claimed to be more real, more sexual, and more in touch with the chaotic messiness of life. And though Ritts would remain one of the industry’s top photographers until his death aged 50 in 2002, it was hard not to detect an increasing disparity between his work and the direction of popular culture.

Ritts always favoured the sacred over the profane. The trend now is not so much to reverse that idea, but to present both on equal footing. Take, for example, Michael Thompson, Phil Poynter or even Hedi Slimane, who employ similar subjects and techniques – shadow saturated supermodels, rock stars, and celebrities in black and white – but who offer a much darker vision of beauty, filtered through a grime-stained, postlapsarian lens. It’s Dostoyevsky rather than Dickens. Ultimately, Ritts’s contemporaries like Ellen von Unwerth and Peter Lindbergh have had far more influence over modern photography.

And yet despite this, or maybe because of it, Ritts’s work still holds up as a sumptuous reminder of a much less complicated time. A time before the three-minute celebrity or the social media superstar, when celebrities were still remote. In this postmodern age, when everything must have a meaning behind the meaning, and when we’re never quite sure whether the artist is having a laugh at our expense, Ritts reminds us that it’s OK to appreciate beauty for beauty’s sake.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion