Number 10 Peironcely Street has seen better days. The fresh white paint that coats a warren of long, narrow patios can’t hide the fact that its walls are crumbling, nor can the cover on the well or the rusty manholes keep the rats and mosquitoes at bay.

But it has seen far worse days. In the winter of 1936, the working-class Madrid district of Vallecas in which it stands was pummelled by the bombers that Hitler sent to help Francisco Franco overthrow Spain’s republican government – and rehearse the blitzkrieg tactics later used in the second world war.

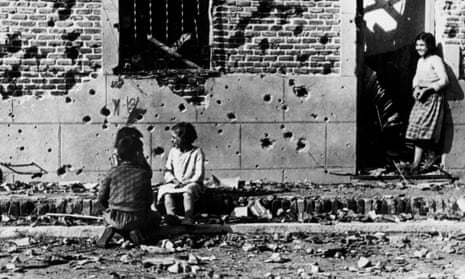

Also there, Leica in hand, was Robert Capa. In one of the most famous pictures of the war in which he forged his reputation, the Hungarian photojournalist captured the civilian consequences of the bombing. On the pavement outside the single-storey building, amid the rubble and in front of a shrapnel-chewed facade, sit three children while a woman looks on from the doorway.

The photograph, which Capa took in November or December 1936, appeared in the US, Swiss and French press. Not only did it reveal the deliberate targeting of civilians, it encouraged international volunteers to travel to Spain to join the civil war to fight Franco’s forces.

Today, more than eight decades on, a campaign is under way to have the rundown building protected and declared part of the Spanish capital’s heritage. According to José María Uría of the trade unionist Fundación Anastasio de Gracia, which is coordinating the conservation effort, Capa’s image has acquired an almost legendary status – not least because it was suppressed in Spain during the dictatorship.

“It’s the first image in history that shows the effects of bombing on the more fragile part of society: children,” he says. “It’s not just part of this country’s memory – although it took 40 years for the pictures to be seen here – it’s part of Europe’s memory. It was the impact of this photo that led many people to get involved [in the war].”

With the support of a coalition of international organisations including Germany’s Goethe Institute and the American International Center of Photography – founded by Capa’s younger brother, Cornell, in 1974 – the foundation is hoping to preserve the building. But, equally importantly, it also wants to help those now living behind the still shrapnel-scared walls of No 10. Just as it was when the picture was taken, Vallecas remains one of the most deprived – and fiercely leftwing – areas of Madrid. The block’s 15 small flats, which range from 17 to 28 square metres, currently hold 14 families. Most have only two tiny bedrooms, forcing parents to sleep on sofas so that their children can get a better night’s rest.

Sonia Suárez, who has lived in the building with her husband and two younger children for the past five years, pays more than €300 (£260) a month to live in a home where the disintegrating walls are damp in winter and boiling in summer. The plumbing is shot and the flimsy wooden front door shrinks and expands with the weather. “Things are bad,” she says, pointing to exposed electrical wiring, and peeling back cheap plastic strips to reveal the rotting brick and cement beneath. “There are no windows in the bedrooms, so you can’t breathe. We want to get out and find a decent place to live.”

Suárez only found out about the building’s history after she moved in. A fellow tenant, who died two years ago at the age of 90, was the daughter of a couple who lived in the block when it was bombed.

It’s odd, she says, to think of her children playing in the same spot as those Capa photographed. “We had no idea all the holes were from bombs; looking at the pictures now sends a shiver down your spine.” As the family understands on a daily basis – and as Uría points out – some things in Vallecas haven’t changed since the winter day when Capa peered through his viewfinder.

“The situation of Sonia’s family and of all the residents of Peironcely 10 is something that our society can’t allow. Keeping these people in this state of neglect drags us back to the Spain of 90 years ago, when the building went up and there was no social protection from the government.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion