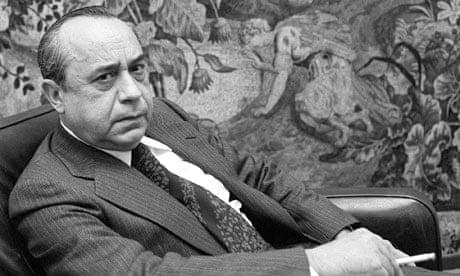

Novelist, essayist and radical politician Leonardo Sciascia was known during his lifetime as the "conscience of Italy" for his unflinching censure of Italian society, its law enforcement, politics and mafia influence. A Simple Story shoots at his customary targets, but castigates them in a more playful fashion than in most of his works.

The volume comprises two short novellas, the first of which, written shortly before Sciascia's death in 1989, is the "simple story" of the title; however, like most stories that commence with the discovery of a body, it is far from simple. The unlikely looking suicide of a diplomat is swiftly followed by two murders, an art theft and a police superintendent behaving very oddly, while the callow sergeant trying to piece together the truth is met by obfuscation at every turn.

Just 40 pages long, it's a pithy murder-mystery with a denouement that, though satisfying, remains somewhat inconclusive, as befits the author's notorious scorn for the Italian justice system. Throughout, the influence of Sciascia's fellow Sicilian Luigi Pirandello is clear, as all too real fury is transmuted into drollness. This arch tone continues in the second novella, "Candido", a take on Voltaire's Candide, which first appeared in 1977. The hero Candido is sanguine and guileless, but his circumstances are far from utopian: born in a cave in Sicily during a bombing raid, his father a perfidious lawyer and his mother a fascist general's daughter who deserts him for her new man, he is unloved and surrounded by communists, fascists, priests and peasants who have nothing but corruption in common. The story is as sprightly as its hero, but Sciascia afterwards notes lugubriously that he failed in his ambition to emulate Voltaire, finding it impossible to satirise optimism when "our times are heavy, very heavy".

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion