“Relationships are vexed”, writes Kate Legge in the early pages of her new book.

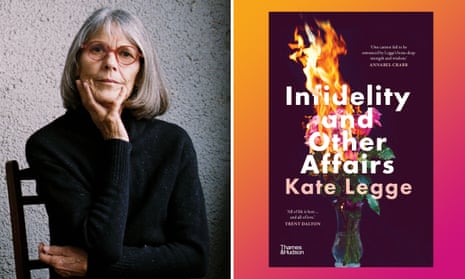

Legge has explored themes of love and marriage in her fiction before – 2006’s The Unexpected Elements of Love was longlisted for the Miles Franklin Award. But in Infidelity, Legge – also a journalist – uses her own experiences as the raw material, turning her reporter’s eye towards the infidelity of her husband, the former chief executive of Fairfax media, Greg Hywood (who she doesn’t name), and then, later, the infidelity of her son. Through that personal prism, she looks at the phenomenon of infidelity more broadly – the science and culture of it, the theories that surround it.

The book opens with a somewhat bleak summary of infidelity: how frequently it happens, right under our noses, suggesting we are almost naive not to expect it. Legge uses this as a set-up for a moment of sharp introspection – she didn’t expect it until it happened to her; even as it continued to happen. When she discovered that her husband was having an affair with her close friend, Legge threw herself into work, reminding herself that she is not the story. It is a powerful act of reclamation, then, to write this book in which she is the story. Infidelity and Other Affairs is unflinchingly personal – while Legge doesn’t name Hywood directly in the book, she hides very little about the aftermath of the affair on her sense of self, and is equally honest about how deeply she values the friendship the two have since navigated.

But the book is also much bigger than just her story. When she discovers that her son has also been unfaithful in his marriage, Legge asks whether a tendency towards infidelity might be inherited, and begins the work of excavating what she calls “the vein of betrayal” that runs through her husband’s family. In the book’s early chapters, she finds a pattern: her husband’s father was unfaithful too, and her husband’s father’s mother. Legge interrogates the behaviours of both the men and the women, and strives for honesty in telling their stories, and there’s a resulting fearlessness to her writing, a promise that she’ll leave no stone unturned – “I want the flesh, the muscles, the tissue and sinewy strings. I’m after the complexities of rogue couplings that the word ‘affair’ doesn’t get close to encapsulating.”

The book is Legge’s grappling with the complexities of infidelity, as she tries to balance her emotional response to her own experience with her intellectual response to science and expert theories. She is particularly interested in the work of famous couples therapist Esther Perel and sex advice columnist and podcaster Dan Savage, who both suggest we need a more nuanced view regarding faithfulness in relationships. Legge returns to the theory that infidelity passes from one generation to the next, but she examines her husband’s history with even-handedness, giving air to the knotty realities of responsibility, failure, loyalty and desire rather than favouring an easier binary of betrayer/betrayed.

The balance of intellect and emotion makes Infidelity easy to read and empathise with. Legge supports her narrative with research and statistics without being heavy-handed – she’s not trying to win points here, or allocate blame, but to reflect on the way that our behaviours and identities are shaped by the affairs (romantic and otherwise) of our ancestors. There’s a sense of genuine and generous curiosity elevating what might otherwise have been a single-sided story of heartbreak.

But for all of the book’s balance, and despite the critical lens Legge applies, there is a blind spot. In making a case that infidelity is or can be an inherited trait, she reduces the influence of the people who don’t fit that thesis: the parents of a cheater who weren’t unfaithful, the chosen family or close friends that were, and the other significant relationships that can impact who we become.

In the second part of the book – Birthmarks – Legge explores the marks left on her identity by her own family, examining with the same forensic detail and empathy her mother’s swings towards mental illness and depression, her brother’s “hostile dependency”, and how they have shaped how she loves and responds to love. She’s no saint in these pages, and is just as uncompromising when she shifts her gaze to herself – the way her tolerance towards her brother has weakened over time, for example, or the self-inflicted violence following her husband’s affair. Legge turns to the culture of silence and shame that’s passed down maternal lines in regards to women’s bodies – and how that strips some women of agency and choice when it comes to intimate affairs.

Legge describes this work as a sort of “literary bricolage” – a narrative made up of a range of available things. While this is more or less true of many works of memoir and creative nonfiction, the book collects itself as stories, research, history and memoir around a central theme, rather than following a specific linear thread. This layering allows Legge to find patterns not only in infidelity but in family and obligation, loyalty and forgiveness and even, towards the end, climate change.

The “other affairs” inferred by the book’s title are far reaching – and the final third of the book, Wisdom Spots, casts an even wider net. These closing essays, which span the varied interests of Legge’s later-life independence – exploring who she is outside her familial relationships – are slightly less absorbing without the emotional propulsion the book begins with, but are interesting nonetheless. Psychologists often talk about three “minds”: the emotional mind, the intellectual mind and the wise mind (a combination of the two). Perhaps this final portion is a journey towards this wise mind, where dualities and contradictions might exist side by side.

“Though I live alone I’m not alone,” she writes, “and I’ve come to relish doing pretty much as I like, when I like, at an age when disinhibition is dangerously alluring.”

Ultimately it’s this disinhibition that is so mesmerising. In revealing the imperfections and damage in her own makeup, Legge invites us to look at our relationships and ourselves more expansively, to take in and grow around the messy realities of our lives.

Infidelity and Other Affairs by Kate Legge is out now through Thames & Hudson

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion