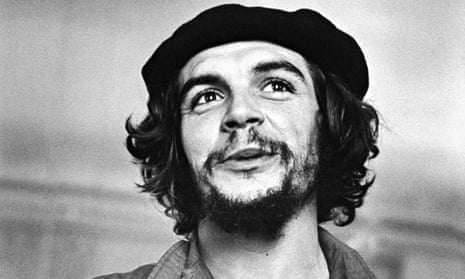

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara

Not for nothing has the image of Che Guevara stayed a hallmark of revolution and every expression of democratic, radical dissent, in to the 21st century. Behind the T-shirt image lies the reality of a man whose vision of liberation was at once romantic, ruthless, personal, poetic and compassionate. Born to a middle-class Argentinian family in 1928, Guevara explored Latin America’s poverty on his motorcycle while training as a doctor, vowing to fight and change what he beheld, and masterminding Cuba’s revolution as a vision for the world. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, a biography by Jon Lee Anderson, the man who located Che’s body in Bolivia, depicts a complex but total revolutionary, as undogmatic as he was committed.

Maximilien Robespierre

Among the historical figures after whom the French name boulevards and squares, one is inexplicably rare: the father of their republic and all modern revolutionary politics. History has given Robespierre a bad rap for his role in what it knows as the Terror. A great orator with a brilliant mind, but an ascetic man, Robespierre drove the great French Revolution, opposing Girondin revolutionary factions that disastrously declared war on the rest of Europe. The wars, and betrayal by others, required Robespierre to defend that revolution with a device proposed along with his friend Joseph-Ignace Guillotin as a humane alternative to the breaking wheel, after the pair had unsuccessfully attempted to abolish the death penalty. Robespierre was guillotined without trial after a coup d’etat on 28 July 1794.

Rosa Luxemburg

History happens, but only just. What would the 20th century have looked like if the German leftist insurgency of 1918-19, in which Luxemburg played her part, had succeeded? No Hitler? No Stalin? A naturalised German of Polish-Jewish origins, she co-founded the Spartacus League, which opposed the first world war and later became the German Communist party. Luxemburg took a passionate stance against both Bolshevik authoritarianism and failed reformism and forged a path that has inspired others ever since, and criticised the violence of the second uprising in 1919, after which she was arrested, tortured and shot.

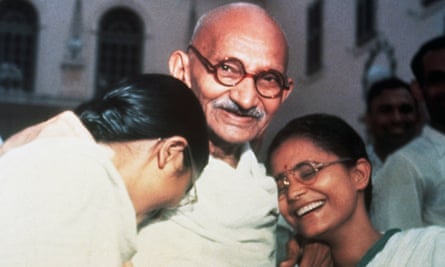

Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi became the guru and inspiration of nonviolent resistance, after deploying its tactics and principles to lead India’s independence from imperial Britain. Born to a Hindu family, he first experimented with nonviolent resistance in South Africa, before returning to India to organise peasants and workers against land taxes and subjugation. Gandhi’s vision was political peace as expression of personal peace, fasting and self-purification. Serially imprisoned, he set an example of resistance to British rule and triumphed, though he rejected the partition of Pakistan and India, of which he is seen as the founding father.

Toussaint L’Ouverture

Haiti may have been one of the world’s most desperate places in recent times, but its proud origins were those of the greatest revolt against slavery since Spartacus, the gladiator and original revolutionary, escaped to march on Rome. Toussaint was leader of the remarkable revolt in 1791 in the then-French colony of Saint Dominique, for which he was nicknamed “Black Spartacus”. Toussaint, himself a free black man and a Jacobin, led the revolt in advance of revolutionary France’s abolition of slavery in 1794. He devised a new constitution for the colony in 1801, and although he stopped short of declaring independence, Napoleon Bonaparte sent troops to re-establish French control. Toussaint was arrested and deported to France, where he died.

Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones

It’s strange to think that a century ago the US was a hotbed of radical syndicalism. Mother Jones, known as “the most dangerous woman in America”, was a teacher and dressmaker, driven from County Cork by famine to Canada, later moving to Chicago. She lost her husband and children to yellow fever and became an organiser of the United Mine Workers union before co-founding the group Industrial Workers of the World. An irrepressible firebrand, she fought against child labour and co-ordinated strikes by miners and silk workers. As a woman who organised men, she was denounced in the US Senate as “grandmother of all agitators”.

James Connolly

Connolly is acclaimed as one of Ireland’s founding fathers, but is insufficiently regarded among the great European revolutionaries of all time; no one has entwined the politics of labour and of national liberation like Connolly. Born in Edinburgh in 1868 to Irish parents, he served in Ireland for the British Army, towards which he conceived a lifelong loathing, and deserted. He founded the Irish Socialist Republican party and, returning to Ireland in 1910, joined Jim Larkin to organise the transport strike of 1913 that led to the Easter Rising three years later. His Irish Citizen Army formed part of the rising, after which Connolly, along with 14 other rebels, was executed by the British.

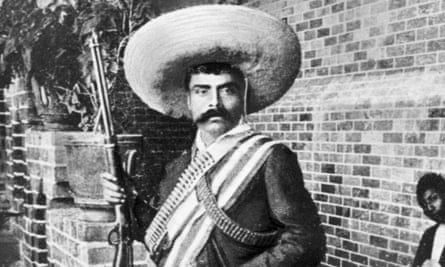

Emiliano Zapata

Hero, with Francisco Villa, of the Mexican revolution of 1910. Influenced by the anarchist communist writings of Prince Peter Kropotkin, Zapata was a warrior for peasant land rights; his Plan de Ayala is the historical template for democratic land ownership. Zapata’s Liberation Army of the South continued to struggle against landowners even after the revolution had installed its political leaders in power. From his base in Morelos, modelled along his revolutionary ideals, Zapata likewise opposed the power of the federal army, which tricked him to his death by feigning a defection. His ideas inspired the neo-Zapatista movement in southern Mexico during the 1990s.

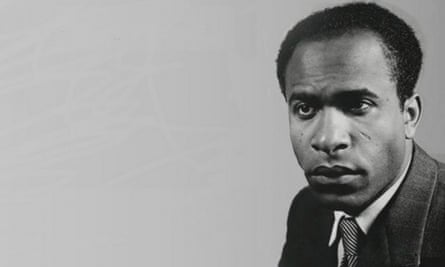

Frantz Fanon

Born in 1925 in Martinique and descended from slaves, Fanon was a psychiatrist and philosopher who arrived at his revolutionary humanism through vivid experience of French colonialism in Algeria. He fought in the French Resistance during the second world war, but was “bleached” along with other non-whites after the end of hostilities. He studied medicine and psychiatry in Lyon, then worked at Blida psychiatric hospital in Algeria. His books Black Skin, White Masks and later The Wretched of the Earth are seminal texts on all colonial violence and inspired the struggle for Algerian independence and thereafter all anti-colonial liberation movements. Fanon was condemned to deportation, but fled to Tunis, later dying of leukaemia in America in 1961.

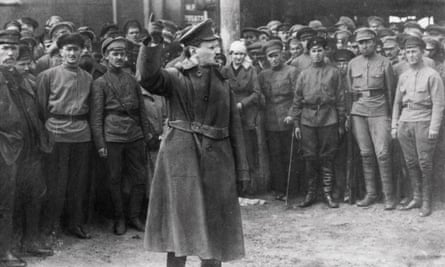

Leon Trotsky

Trotsky was the architect, along with Vladimir Lenin, of the Bolshevik Russian revolution of 1917, and victim and symbol of that revolution’s transformation into Stalinism. Born Lev Bronstein to a Jewish family in Ukraine, Trotsky spent much of his youth as an agitator in exile, returning to join the uprisings of 1905 and the revolution of 1917. He took charge of the Red Army in 1918. With Stalin’s accession, however, Trotsky became part of the Left Opposition, coming into conflict with Stalin on, among other things, his commitment to global revolution versus Stalin’s authoritarian “socialism in one country”. Increasingly marginalised and eventually expelled from the Central Committee, he fled first to France, then to Norway, eventually moving in to the house of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera in Mexico City. In 1940, he was traced to the city and murdered by Stalin’s agents.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion