In Matthew McConaughey’s new movie, Gold, he plays a man whose characterisation he loosely based on his father. That character, Kenny Wells, is himself based on a real person, a businessman who in the early 1990s struck gold in Indonesia and was briefly worth $4bn, before the deal catastrophically derailed. In the actor’s mind, that shambolic entrepreneurism is typical of what the movie calls “the hustlers, the scrappers, the make-it-happen muthafuckers”. Just like Jim McConaughey.

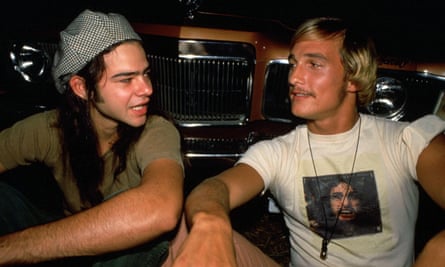

It is a long way from McConaughey the hustler’s child to the sleek actor before me in a New York hotel room. Now 47, McConaughey stretches out in his chair, limbs splayed, a lazy smile on his face that he keeps just this side of a smirk. For a long time, his public image was closely identified with his first movie role, as Wooderson, a good-natured stoner in Richard Linklater’s Dazed And Confused. In the early to mid-2000s, he made a slew of romantic comedies in which he bounced around on the beach or trailed young ladies through the streets of Manhattan, with an easy charm that both enhanced and circumscribed his appeal. Then McConaughey entered a third phase, widely characterised as his big gamble to be taken seriously, but which he says was a “life vest” at a time when acting had become deeply uninteresting. After a few small, dark films it culminated in his 2014 Oscar for Dallas Buyers Club.

For the making of Gold, McConaughey gained 45lb, wore a bald cap to make his hair appear thinner and put in a set of unflattering dentures, a radical transformation typical of his third act. (He most famously shed almost the same amount of weight for Dallas Buyers Club, and in 2012 piled on the muscle to play a stripper in Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike.) He was also required, for most of the movie, to play lightly drunk, and his depiction of Wells as a good-hearted but ultimately disastrous loose cannon – a man who burns through a lot of other people’s money – is hard to resist. “I know a lot of people – and I don’t care for what they do, I wouldn’t trust ’em with my kids, or round my family – but boy, I respect who they are,” says McConaughey. “Kenny Wells was one of those guys. That’s just who he is. You can say, ‘Oh he’s such a scallywag.’ But oh, man. He’s pure.”

When he first read the script, McConaughey became convinced he had a unique insight into Wells’ character. His father, who died when McConaughey was 21, was a highly successful entrepreneur in the oil business, selling lengths of pipe, among other things. His elder brother went into the family business and McConaughey himself spent a summer on the phone selling advertising. If he needed this kind of connection with every movie he made, “I’d only have made three films,” he says. But in this case, he knew instantly and to the last molecule who Kenny Wells was.

It was his father who taught McConaughey to go for the interesting in life over the secure, and in conversation his depiction of him, which is fond and mildly satirical, indicates how much of his own style comes from mimicking his dad. “Oh, man, he was a ham,” he says, hammily. “Peddlin’. That’s what he called it – peddlin’; we’re peddlin’ pipe. And I remember my brother, who worked for him, would get there at 7.55am, walk in, say hi, and at about 8.01 my dad would say, goddamn it you’re supposed to be on the phone from 8am, not 8.01.”

In the early years of McConaughey’s childhood, the family was rich. There were speedboats and jets bearing his father’s company logo. Money was flowing through the Texas oil industry at such a rate, says McConaughey, that his brother was a millionaire by 22. “They’d go to the bar at 2pm because people wanted to do business with someone they liked to have a drink with, and they’d make $50k, just like that. One of the great images I have of my father is on the phone with a cigarette – at the airport, on the pay phone, always peddlin’.”

The crash of ’82 almost wiped him out, but McConaughey senior never let on. He died of a heart attack 10 years later, and it was only after his death that his son discovered how close to bankruptcy his father had been. It was an odd sensation, he says, discovering that behind all that bluster, behind the terrific performance, he was barely getting by. “First reaction is, ‘That son of a bitch!’” he says. The second reaction was a slow-dawning admiration. “He’d wake up every day and say, ‘Today’s going to be the day, buddy!’ And his other line was, ‘I’m gonna hit a lick! I’m gonna get a big sale. Let’s hit a lick boys, let’s hit a lick!’ And he never did for those 10 years. But he had a resilience and an appetite. He was consuming life.”

It was out of this background that McConaughey pulled Kenny Wells, whose well-finessed self-delusion gets thousands of people to part with their money. “People invested those hundreds of millions of dollars on the story. What makes the story move?” McConaughey smiles his lazy smile. “Confidence.”

For a short period in the early part of his career, McConaughey was at risk of becoming obnoxious. He’d fallen into acting almost by chance: the casting agent for Dazed And Confused, who was scouting in Austin, auditioned him on the basis of a random conversation when they met at a bar. McConaughey was still a student at the University of Texas, studying film and TV, and after the film came out his instant success somewhat stunned him. He was young, feted, on billboards throughout Hollywood, and within a few years his location packages started to include fringe benefits that blew his mind. He was given a staff that included a maid – “and she cooks!” he says, reliving the amazement. “She leaves me a meal! And, check this out, she irons my jeans!” There is a long pause. “I hated that crease in my jeans.”

It wasn’t his style, and before long McConaughey started to feel alienated. “I felt drama being created that wasn’t real. I felt uncomfortable, like I had to sit on my hands and go, if I don’t ask that person to do something then they have nothing to do.” And then there was the problem of his mother. If McConaughey talks about his father with a combination of indulgence and affection, his mother, Kay, still has the power to astound him. She and his father married three times and divorced twice. “They were fun, man,” he says, shaking his head. They would invest in a diamond mine and disappear down to Ecuador to inspect it, only to discover there weren’t any diamonds. “The whole family would rather invest in something that sounds as if it could be wild and fun, and make a quarter of the money, than do a straight deal with a bunch of squares that wasn’t going to be as fun.”

This was all well and good when the fun was in Latin America. But when McConaughey became famous, his mother took a shine to the idea of a Hollywood life and started pestering him to let her hang out on set. Even at the best of times, he says, she wasn’t relaxing company. “Mom would say, ‘Don’t walk in a place like you wanna buy it; walk in like you own it.’ That was Mom’s deal. She was all offence. Brash. If anything’s going smooth for 15 minutes? Bam! Controversy. Gets her fired up. No smooth road.”

In those early days of his fame, he admonished her: “If I was in Chicago, being an accountant, would you want to come see me as often?” She brushed his objections aside, “to the extent that it wasn’t an easy relationship for a while. It was the first time for me, going through it, trying to find my balance of newfound celebrity, and I remember saying many times to my mom, ‘I don’t need a hang-on buddy right now.’”

He also didn’t need her inviting the press into the family home. “I said, ‘Next time they want to come to the house to get a tour and hear about my childhood, just check with me?’ She said, ‘OK, OK.’ A week later, a phone call. On Channel Seven, Hard Copy, my mom’s walking a camera guy through my bedroom saying, ‘And this is where he had, I think, his first sex.’ I call her and she goes, ‘I didn’t think you’d see that.’”

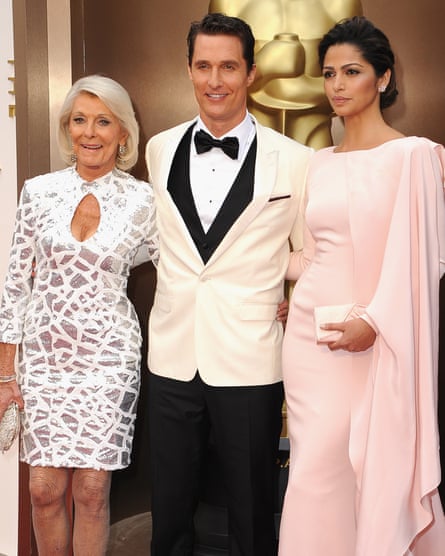

Kay McConaughey is 84 now and her son relates all this with an amusement just about stripped of irritation. He encouraged her to write her own memoir, which she called I Amaze Myself; it includes a chapter entitled Some People Deserve To Be Pissed On. McConaughey wheezes with laughter at the mention of this. It is, he says, hard to take oneself too seriously with these kinds of folk in one’s background. If he’d ever really started to play the movie star card, “Every time I went home for a holiday I would’ve been pounded and humiliated. My family is so good if anyone gets on their high horse – they will just dominate you till you say uncle. Then they’ll pick you up and get you a drink.”

Eventually, after those first unsettling years, he found his level. Now, when he goes on location, he takes a backpack. “It’s as stripped down as it gets. I live in my trailer. I wake up and I’ve got a pair of pyjamas and one pair of pants. I have a singular focus. And thankfully I have a wife who says, ‘Don’t look in the rear view mirror. Go ahead – we’re here.’ My family comes with me, so I don’t have that separation – of going into the debit section in your relationship with your wife or your fatherhood.”

McConaughey’s wife, Camila Alves, is a Brazilian model and designer whom he met at a nightclub in Hollywood in 2006. They have two sons and a daughter, Levi, Livingston and Vida, and it’s no coincidence, says McConaughey, that it was while Camila was pregnant with their eldest child, Levi, that he started to reassess his career. In the late 2000s, he had been solidly and lucratively employed in a series of paper-thin and highly enjoyable romcoms, chief among them The Wedding Planner, with Jennifer Lopez, How To Lose A Guy In 10 Days, co-starring Kate Hudson, and Failure To Launch, with Sarah Jessica Parker. “You know the story,” he says. “Boy meets girl, we break up in the middle, boy chases her down at the end and meets her on a bridge or a moped. But you want to enjoy who you go there with, the male and the female.”

The slightness of those movies doesn’t detract from their charm, and, watching them now, it seems to me that they are probably harder to pull off for an actor than heavier material. (This month he also voices the koala lead of the new kids’ movie, Sing.) True, says McConaughey. “They are thin, by design. You come in on a cloud and you skip from cloud to cloud, and if you drop anchor in a romantic comedy, you will sink the ship. If it’s a scene where boy meets girl and I get really mad for a second, uh-uh, cut. ‘You can’t get mad because we won’t believe you can make it back.’ That’s how it goes. No, no, no. What’s easier about a drama is that: with every question, you can hang your hat on what would this character humanly do? You’re looking for reality all the time. You don’t go pining for reality in a romcom. You’re supposed to stay up there and bounce.”

After making enough movies in this vein, McConaughey inevitably grew bored. “The ceiling and the basement of your emotions – how much pain can I feel, how happy can I be, how loud can I laugh? – that’s designed to be a very thin wavelength, much closer together.” Still, it was hard to walk away. The money was so good that for a while he could kid himself he was getting something out of it. “That same script, same words, with a $5m offer, is so much better written than the one with the $1m offer.”

It is more common to see female actors rebrand in the same way as McConaughey (Charlize Theron, Reese Witherspoon, say) since so many women in Hollywood start out in generic romantic roles. The first thing McConaughey did was to talk to his managers and warn them he wasn’t going to work for a while. (He’s never been someone to line up five jobs in advance – it makes him feel boxed in – so after Ghosts Of Girlfriends Past in 2009, he had a clean slate.) Then he talked to his wife, who was supportive. Then he started the long, hair-raising process of saying no to every script that came in, followed by the even more hair-raising period of sitting on his hands while nothing came in at all.

“So the anxiety was, well, how long is nothing going to come in? Having a family helps, but I feel like I always need to be accomplishing something, for my own happiness and significance. I gotta work. The anxiety was in how long will it be dry, how long will we get nothing? My agent did a good job saying no, no, no. Then the studios got the message and quit sending them. Then there was an impasse of nothing. And there was nothing for about eight months.”

He tried to enjoy the novelty of fear – although it should be added that fear in this context is entirely relative: McConaughey wasn’t going to end up on the street. “I have an affluent life, my rent’s paid for, we’re not going to go hungry,” he says. Still, the experience of being out of favour with Hollywood was deeply unnerving. He thought, “This shakes my floor a bit.” He waited and waited. He wrote down a motto on a piece of paper, which he referred to whenever he felt his nerve giving way. “I wrote, ‘Fuck the bucks – I’m going for the experience.’” And so when, finally, the script for William Friedkin’s gothic thriller Killer Joe came in, McConaughey was ready.

This – and the small films that immediately followed, Soderbergh’s Magic Mike and Jeff Nichols’ Mud – were a whole new filming experience for McConaughey. The budgets were low; there weren’t 25 layers of management. There were no studio executives to police his behaviour, which had been a source of at least theoretical concern since 1999, when police in Austin arrested him for disturbing his neighbours by playing his bongos – naked – in the middle of the night. “No one’s going to interfere,” he says. “No one’s going to say, ‘Don’t smoke so much.’ We’re not having that conversation. There was a freedom.”

The funny thing is, he went about preparing for these heavy roles in exactly the same way as for the silly ones. McConaughey has a studious streak and, before walking on set, he makes hundreds of pages of notes on a character, whittling them down until they are a few key phrases that represent his idea of the role. “People would say, ‘He used to just roll out of bed and go, “Just keep livin’, dude!” And now he got serious.’ No. I had just as many bookmarks and notes in those romcoms as in True Detective or Dallas Buyers or Gold.”

Released from the constraints of the romcom format, he found himself drawn to a certain type of character. There is something that links Ron Woodroof, the cowboy in Dallas Buyers Club who hustles medicine to help himself and other people with Aids, with Kenny Wells and the eponymous hero of Mud. “The actors I’d always liked, and the people I’d liked, are these kind of outcast characters on the fringes – the antiheroes, who have a whole lot more identity than the hero. The anti-heroes aren’t placating and pandering; they can go right through the slipstream.”

The physical transformations he frequently undergoes can look like a gimmick, the “uglifying” process seen as a pretty actor’s bid for Oscar consideration. McConaughey had a lot of fun bulking up for Kenny Wells and slimming down for Ron Woodroof – in fact, during the crash diet for the latter, he felt “on fricking fire. All the power I lost in my body got sublimated up here. I needed three hours less sleep a night. Almost clinically sharp. Kind of hard to be around.” But he’s not “looking for an eccentricity or an aberration. I’m not looking for a reason to be fatter.” And his vanity isn’t piqued by the transformation. “I would be more vain if I didn’t commit. I’m so vain that I don’t want to be embarrassed.”

There is something so nakedly cheesy about McConaughey’s style that it gives him a weird kind of sincerity. This is never more apparent than when he talks about wanting to “give something back”, usually an eye-rolling moment, but in his case a prelude to something convincing. He wanted to help kids and realised that high school is the last opportunity to fail without going to prison or being pulled up short in worse ways. So he set up a charity that funds safe after-school places for children in low-income neighbourhoods. It now has dozens of locations across the US. There are health and nutrition classes: “We ask them: ‘What did your mom spend last night on six burgers and fries? $35. Let’s take that $35, go to the supermarket and spend the same amount of money on a healthy meal, but also you get to cook for your family.’” There’s a community service element, which McConaughey thought none of the kids would go for: “I wouldn’t have given you my Saturday in high school.” But they did. “The idea of getting on a bus to go to the beach to do a beach clean-up? They’ll do it because they’re getting out of the neighbourhood.”

His favourite part, however, is the “gratitude circle”. Sometimes McConaughey drops into one of the sessions, to disabuse the kids of the idea it all has to be embarrassingly uncool. “I came to one class one day and said, ‘Look, I’m thankful that I woke up this morning and I got a great kiss from my wife.’ And then a girl goes, ‘I’m thankful that I’m so sexy!’ And someone’s grateful that Halloween’s coming. I’m like, ‘Yes!’” It has, perhaps, taken him a long time to say this and really mean it. “It doesn’t have to be heavy stuff.”

Gold is released on 3 February in the UK, and 2 February in Australia. Sing is out now.

Guardian readers who are also cinema fanatics can find Odeon discount codes by visiting discountcode.theguardian.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion