/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/72943234/hayao_miyazaki_ringer_illo_2.0.jpg)

A great deal of the buzz for The Boy and the Heron concerns the once-teased, then-retracted retirement of the movie’s director, Hayao Miyazaki, the acclaimed cofounder of Studio Ghibli. This is, admittedly, the prospect often driving discussion of Miyazaki, who has been false-starting his retirement since 1997’s Princess Mononoke.

Ten years ago, The Wind Rises was billed as Miyazaki’s swan song; it was a grounded and mature semi-biography of the aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi, who designed the iconic Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” and served as an inspiration to Miyazaki, who famously loves planes. But then, a few years after The Wind Rises, Miyazaki returned to direct Boro the Caterpillar—a short film, yes, and limited to screenings in Japan at the Ghibli Museum and Ghibli Park, but also a clear sign of the director’s restlessness.

Now, it’s 2023, Miyazaki is almost 83 years old, and the gaps between his major releases are conspicuously wide: five years between Ponyo and The Wind Rises and then 10 years between The Wind Rises and The Boy and the Heron. Five years ago, Miyazaki’s early mentor and Studio Ghibli’s cofounder, Isao Takahata, died, aged 82, from lung cancer—a grim reminder of Takahata and Miyazaki’s shared smoking habit. “It makes me think my time is also limited,” Miyazaki told mourners at a public memorial service for Takahata at the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka.

Miyazaki is an unlikely hero to so many different corners of culture—cinephiles, middle schoolers, weebs. At some point in the past decade, despite his limited output in that span, Miyazaki became something more than the director of some beloved children’s movies. That’s effectively how Disney introduced Miyazaki to North America when the company partnered with Studio Ghibli in the ’90s and began distributing its movies outside Japan. The ads for Spirited Away, which ran after the movie won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, invoked the director in very august terms usually reserved for homemade classics going into the so-called Disney Vault: From master filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki …

The marketing was a sign of the times. Anime was a hard sell in the U.S., and even the most prestigious theatrical anime of the preceding decade, Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell and Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, were extremely risqué by the contemporary standards of American cartoons. Spirited Away also came at a time when Japanese animators, in television especially, were starting to dabble in modern “digipaint.” Studio Ghibli, with its hand-drawn animation, thus represented a more nostalgic and pastoral outlook on anime. And that idea continued to stick. Back in 2016, The Ringer ran a package celebrating a group of elite performers and creators in sports and popular culture—the so-called Undeniables—and in one of those essays, I hailed Miyazaki as a master craftsman whose studio produces the last great works of traditional animation.

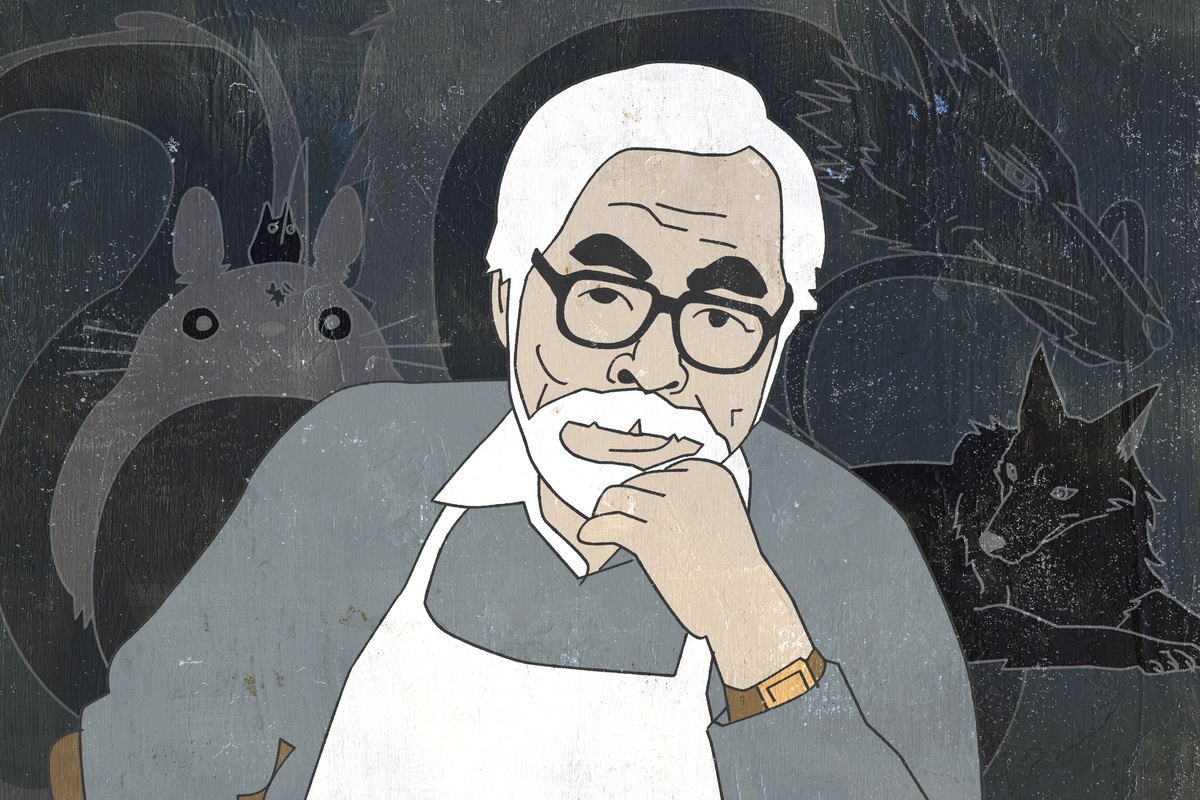

This is one way to talk about Miyazaki, and it’s all well and true, but these days, I find I’m more preoccupied with the image of Miyazaki himself: the old man with the white beard and the dark eyebrows and the square frames and the sooty apron, speaking Japanese to a documentary cameraman as he smokes his Seven Stars. This is Miyazaki at work, yes, but this is also the Miyazaki who has become a sort of embodied meme in the internet age. So much of the mythmaking about Hayao Miyazaki in the West happens in the viral apocrypha. These are screenshots of video footage from an interview with a Japanese news website, The Golden Times, in the downtime after The Wind Rises, in which Miyazaki talks about the demands of his profession and the state of his industry. “If you don’t spend time watching real people, you can’t do this,” he says, lamenting the proliferation of so many otaku, or nerd culture superfans with antisocial tendencies, in animation.

The internet has had a field day with this sentiment ever since, and it’s built the man into an exceedingly clever and withering figure. It’s taken other footage of Miyazaki, from Mami Sunada’s documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, and transformed his tough-love critique of otaku into the troll quote commonly, if only jokingly, attributed to him: “Anime was a mistake.”

Most people familiar with this pronouncement know that Miyazaki never actually said this, that it’s satire from some random internet user and easily identifiable as such, as it’s supposedly coming from, of all people, the living god of Japanese animation. Miyazaki is decidedly one of the key figures in legitimizing watching cartoons into adulthood. But it’s nonetheless delightful and conspicuously easy to imagine him saying such things, and this is, I suppose, because he is the rare creator to freely relate to nerd culture in this way: authoritatively, but also critically.

You see this in so much footage of Miyazaki spending time with his most notable protégé, Hideaki Anno, the creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion and the Japanese voice actor for Jiro in The Wind Rises. Over the years, Anno has similarly criticized otaku, but as the creator of a work as beloved as Evangelion, and furthermore the live-action director of revivalist takes on Godzilla and Ultraman, he’s also a hero to otaku and, in some sense, their patron saint. And Miyazaki, in many clips, acts as something of a father figure to Anno—a benevolent ballbuster who has a way of bringing his bashful protégé back to earth. Walt Disney may have felt obliged to adopt a smoke-free and sweet-hearted persona to match the spirit of his cartoons, but Miyazaki is endearing precisely because he’s so utterly sardonic.

There’s no shortage of evidence of Miyazaki’s softer side, too. There’s the viral behind-the-scenes footage of Miyazaki making ramen for the staff in the overtime production of Spirited Away. There’s the entirety of Dreams and Madness, which presents Studio Ghibli and its founding wise men—Miyazaki, Takahata, and Toshio Suzuki—as a family of sorts, ensconced in a whimsical suburban campus in the low-key neighborhood of Koganei. And, of course, most importantly, there’s his animated work—typically quite sweet, gentle, and, as I said earlier, nostalgic.

But then you observe the man at his desk, and you see there’s magic and mischief in every stage of life, through old age and false retirements and apocryphal quotes. You see a man who immortalizes childhood like no one else while also imploring us to grow up.