How a Small Maryland Town Survived the Blair Witch

Missing-person posters and confused whispers swirled around the 1999 Sundance Film Festival screening of a movie claiming to be a compilation of real video footage shot by three hikers who'd been killed under mysterious circumstances. Festival guides made it very clear that the movie, The Blair Witch Project, was, in fact, a work of fiction, but the masquerade made writer-directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez the talk of the festival.

The ingenious marketing plan for The Blair Witch Project's theatrical release made fact and fiction even blurrier, turning a $30,000 indie into a $140 million blockbuster phenomenon, giving rise to an entire "found"-footage subgenre in the process, and convincing a portion of the movie-going population that the myth was real. The thing was, part of the myth was real. Burkittsville, "home" of the movie's demonic spirit, was an unassuming Maryland town. And little did residents realize that Blair Witch hoopla would haunt them for the better part of two decades, all the way through to this year's mysterious new sequel.

Faking history

All myths are born, even the bullshit ones. The "Blair Witch" legend took shape when Myrick and Sánchez mapped out a plan that would culminate in The Blair Witch Project. Step one: a pitch video. Produced in 1998, the faux-educational spot detailed the exploits of a witch named Elly Kedward, who was banished from a colonial town of "Blair, Maryland," when she was accused of trying to let blood from local children. In the late 1800s, a child "went missing" in the forest, and when he returned, one of the search parties was found dismembered. In Burkittsville in the 1940s, an old hermit named Rustin Parr came down from the Black Hills Forest saying he was "finished" -- he'd killed seven children in his woodland home and blamed their deaths on the Blair Witch. The footage from the lost documentary crew was found at the ruins of Rustin Parr’s house.

Ben Rock, who would go on to be the production designer on The Blair Witch Project, recently recalled the mythology's origins, admitting that he was "a little obsessed with anagrams back then." Rock took the name of British occultist Edward Kelly (who, along with John Dee, was said to bring dead people back to life) and wound up with the witch's "name." Rustin Parr's name began as an anagram for Rasputin. With a backstory sketched out, Myrick and Sánchez were free to drop victims into the middle of it.

Before Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard "disappeared in the Black Hills Forest in 1991," Myrick and Sánchez needed a starting point. That's where the trouble started for Burkittsville, MD.

Making history

Burkittsville proclaims itself "a town rich in history and surrounded by beauty." In 1999, there were only 75 houses, a post office, and a church within the town limits. Locals call Main St "a testament to a simpler way of life." One would barely find a crossed look in Burkittsville, MD, let alone a terrorizing ghoul.

The Blair Witch legend blossomed in Burkittsville because of a cemetery. Just 50 minutes from The Blair Witch Project crew's Germantown, MD base, the town was the site of the September 1862 Battle of Crampton's Gap, one of the minor skirmishes leading up to the Battle of Antietam, fought three days later. The only remotely "creepy" aspects of Burkittsville were "Spook Hill," an incline just outside of town where Civil War soldier ghosts supposedly pushed idling cars uphill late at night, and "the Snallygaster," a mythical dragon that once laid an egg in the nearby hills.

In The Blair Witch Project, the real Burkittsville only appears twice: a "Welcome to Burkittsville" sign and several shots in the cemetery behind St. Paul's Lutheran Church, where the "witch's first victims were buried." There wasn't much more of the town to show -- it only takes 15 minutes to walk from one end of town to the other, and according to the most recent census data, its population is a mere 150. Myrick and Sánchez didn't film the Black Hills Forest portion of the movie in Burkittsville because it doesn't have a Black Hills Forest (those sequences were shot in Patapsco Valley State Park).They didn't even find real Burkittsville residents for the testimonials from "Burkittsville residents" -- those were shot back in Germantown. But even an establishing shot has staying power, as those directly and tangentially tied to The Blair Witch Project would eventually discover.

Making more history

"For the record, there never was a 'Blair Witch,' nor was the vicinity of Burkittsville ever known as 'Blair Township,'" Burkittsville's "unofficial historian" Timothy J. Reese wrote in 1999. "Those claiming to have done their homework in this regard had better direct their gullible inquiries to the buffoons who crafted this fictional cinematic nonsense. We locals would appreciate it if they took their fantasies elsewhere."

Those "buffoons" only doubled down after The Blair Witch Project's Sundance premiere. After purchasing the movie out of the festival, Artisan Entertainment commissioned Myrick and Sánchez to shoot additional footage for both the movie (including mentions of Rustin Parr and four alternate endings) and a fake television documentary that would air on the Sci-Fi Channel (now the uber-hip "SyFy") the week the film was released. Julia Fair, an employee of Myrick and Sánchez's Haxan Films, was in charge of creating props representing Blair’s witchy history. Fair created dozens of documents for the film, including the "only" copy of a book called The Blair Witch Cult that serves as the inciting incident for the character of Heather’s curiosity in the film.

"I tried to put it in historical context," Fair told The Baltimore Sun in 2000. "I researched the times and the history of Maryland." The real township of Burkittsville was founded by Henry Burkitt in 1810. In Fair’s history, a railroad magnate founded it on the site of Blair in 1824 so he could exploit limestone deposits in the area (there are no limestone deposits near actual Burkittsville). A year after the film was released, Fair would realize what her thorough job had wrought. According to an April 2000 interview, she swore never to visit the town again after a Burkittsville historian told her, "You're ruining the history of my county."

Blair Witch mania approached Burkittsville like a storm. In the weeks leading up to the July 30th release of the movie, residents received emails from strangers asking about the witch. Postmaster Larry Ott told The Baltimore Sun that he warded off a barrage of phone calls. ("I've been postmaster since '93, and I tell them that if all this had happened in '94, I think I would have heard about it.") The city put its two police deputies on overtime to patrol the cemetery and issued a notification to all residents: "After viewing the movie, people may want to come out and see what Burkittsville is really like. We ask that you be cautious and reinforce safety precautions within your family." In turn, residents started locking their front doors for the first time ever.

Burkittsville mayor Joyce Brown, just starting her second term, was forced to address media attention and defend the town's values. "I've lived here 35 years and have also inquired with some older citizens -- none of them have ever heard of a Blair Witch," she told the Sun. "We are a Christian community. We have two local churches that have been established over 100 years. We take our Christianity seriously."

Shaking up history

When The Blair Witch Project took off with audiences, the mythology-heavy website was still at the center of its ad campaign and pointing to Burkittsville. Tourists from around the country and even across the pond swung by for a taste of mystery. Almost immediately, one of the four "Welcome to the Historic Village of Burkittsville" signs disappeared (Artisan Entertainment would eventually pay $1,143 to replace the sign with one welded to metal poles). Michelle Beller, the town clerk at the time, noticed after-dark activity at the graveyard -- someone was leaving candle luminaries on top of the gravestones. Brown reportedly called the president of the chamber of commerce from Amity, NY (who dealt with a similar craze after the release of The Amityville Horror in 1979), to ask for advice, and was told there was no way to stop the thrill-seekers.

While some residents cowered, others capitalized; Ott, who weeks before spoke out about the fiction, now found himself in the Burkittsville postcard business. "Yesterday I sold about a hundred," he said that August. Local artist Margaret Kennedy painted the movie's logo on T-shirts and sold them out of her Main St art gallery. After a fan posted photos of stolen Burkittsville cemetery dirt online, Linda Prior Millard and her 81-year-old mother Louise started selling "Blair Witch rocks" for $5 a pop. The Priors also made their own "stickmen" figures -- both full-size and refrigerator magnet versions. By the end of August, Linda managed to finally see the movie. "I thought it was pretty stupid," she said.

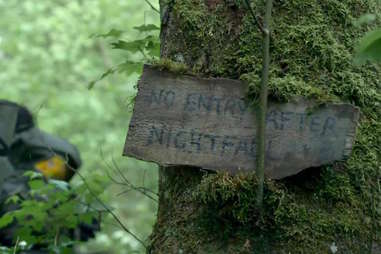

Mayor Brown remained cautious. That October, Burkittsville officially moved trick-or-treating night off of October 31st so the children could grab their candy "without outsiders being involved." Brown eventually conceded to The Blair Witch Project's impact on Burkittsville history by putting a copy of the film in the official town record and welcoming film enthusiasts. "We are friendly to [the fans]," Brown said, "and they, for the most part, have been courteous to us." Across the street from the mayor, someone had nailed a sign to a telephone pole that read "THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT IS TOTAL FICTION." Still, reports indicate that Burkittsville visitors trespassed on residents' private property, videotaped people against their wishes, and caused minor property damage, including a pentagram graffitied on the side of the church. Even residents playing nice were chastised; Deb Burgoyne let curious tourists use the restrooms in her house until someone accused her of jeopardizing her children's lives by living in a town where a witch historically hunts children.

Remaking history

By 2000, the Blair Witch phenomenon appeared to be over, even if reports of 20-somethings recreating the fictitious exploration continued to trickle in ("We've been walking for hours and we can't find a thing!" complained one occult enthusiast to The WashingtonPost). But Hollywood was still possessed; in January 2000, Artisan Entertainment announced Blair Witch 2, with documentarian Joe Berlinger (Paradise Lost) set to pump out the movie for a fall release. One planned stop: a visit to Burkittsville. Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 would follow a meta path, abandoning found footage and beginning with Burkittsville's sudden popularity -- a haunted tale of mass hysteria.

What the sequel's producers didn't anticipate was a Burkittsville ready to air grievances. A Baltimore Sunreport for February 15th paints a chilly picture of Artisan's initial interaction: "When the producers arrived at a town meeting Monday to pitch an idea of filming residents talking about the impact the original movie had on the town, they were repeatedly interrupted and insulted until they finally walked out... Yesterday, only a few residents of this town of 200... would discuss the fracas, and most who did talk wouldn't give their names." (Not that it's hard to identify some of the angrier residents from their previous statements -- it's a small town.)

"They'd come along and be peeking in people's windows, asking them where the witch lived. There were even people holding candlelight vigils in the cemetery for the dead children," said a man who would only identify himself as the town historian. "And they wouldn't believe it was fiction."

Even though Berlinger told the meeting that his movie was a psychological thriller spurred by The Blair Witch Project fake-out, the memories of property damage and invasions of privacy overruled the majority of the meeting's attendees. One of the most shocking statements came from a former town councilman named Sam Brown, husband of Mayor Joyce Brown, who claimed: "We've already been raped, now they want us to be prostitutes." Mayor Brown said she "can't comment."

Despite the mayor barring access, Berlinger managed to shoot a few interviews with Burkittsville residents in the town sometime in the late spring. Linda Prior Millard appears in the film telling the true story of making profits selling rocks and sticks from her house. Deb Burgoyne, no longer offering up her bathroom, tells a story about always having makeup on when she leaves her house because she's being "video'd" all the time.

That October, Mayor Joyce Brown issued another letter to Burkittsville residents, alerting them that, again, a horror movie was coming out that would use the town's name in advertising. Audrey Stadnick, Larry Ott's postmaster successor, started getting about a dozen visitors a day, again asking if the Blair Witch legend was true. The "Welcome to Burkittsville" signs went into storage again (in Blair Witch 2, the character played by Jeffrey Donovan is shown to have been the one to steal the first wooden sign as an Easter egg). The Frederick County Sheriff's Office assigned two deputies to the town for extra security the week of Halloween again. "The only times we'd have anyone specifically assigned to Burkittsville is, well, when we're doing this," said Sgt. Tom Winebrenner of the Sheriff’s Office.

Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 was a critical failure in October 2000, and Burkittsville let out a collective sigh of relief. The only real scare: cease-and-desist letters from Artisan Entertainment. According to a later report, anyone creating Blair Witch merchandise without a license, including local artist Margaret Kennedy (who had been selling T-shirts), received a slap on the wrist. "It scared her so much, she gave all the shirts away," said Deb Burgoyne, the woman who is actually in Book of Shadows.

Eleven years after The Blair Witch Project’s release, the town voted to auction off the metal Burkittsville signs that Artisan had bought for it in 1999. Since, the town signs have been redesigned twice, both times trying to not resemble any sign appearing in any Blair Witch film.

Breaking from history

Over the summer, director Adam Wingard, a favorite of the indie-horror community, unveiled his new film The Woods at San Diego Comic-Con. When the lights went down a surprise lit up the screen: The Woodswas actually a new Blair Witch sequel. Years after Burkittsville made its own reparations by auctioning off studio-bought signs (for much more than the $1,500 they were worth), the fake legend of the Blair Witch looked to surge interest in the community once again.

Much has changed since 1999. The internet is an endless source of hazy truths and debunkery: Paranormal Activity made "found footage" a household genre, and "viral campaigns," movie marketing masquerading as blips of reality, arrive with every new blockbuster. Burkittsville holds strong, vying to be as peaceful as possible. A few horror-film fans still pass through each year. Mayor Joyce Brown is gone, replaced by Mayor Deb Burgoyne (yes, the lady in the big sun hat in Book of Shadows is the mayor now). Most cultural phenomena pass by town; you won't find any Pokémon lurking around Burkittsville. The nearest screening of Blair Witch is an hour away. Judging from the movie's underwhelming $9.5 million weekend box office, few people made the trip.

That doesn't mean the residents didn't prepare. In the days leading up to Blair Witch, "Welcome" signs in Burkittsville were taken down, and side streets connecting to Main were chained off. Mayor Burgoyne directed people to book hotel rooms in nearby Middletown and Brunswick to escape potential frenzy. There's an unwillingness to engage with even the slightest uptick in Blair Witch fandom -- I left multiple messages on the town office answering machine, looking for insight into the post-movie plans. No one responded. Burkittsville was in a minor lockdown. It could be exhaustion. Rebecca Remaley, a resident who lives near the cemetery, was preemptively tired of the new movie. "We're a welcoming community," she told the Frederick News-Post. "There was just those instances where people seemed to forget that actual people lived here." And a witch, some say.

Sign up here for our daily Thrillist email, and get your fix of the best in food/drink/fun.