DADA Manifesto Explained - Hugo Ball versus Tristan Tzara

As in every human endeavor when two strong personalities meet, opinions may clash and an argument often ensues. The same applies to the art world. Dada Manifesto is not a singular writing; over the years several were made, including perhaps the best-known by Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara. Ball wrote his piece in 1916, and dated it July 14, while Tzara’s came a few years later, in 1918, on the 23rd of March. Both Manifestos are explanations of the Dada movement and its goals, but the content differs as long as the modes of spreading the movement throughout Europe and ultimately world, were concerned. These differences actually led to the confrontation between the two authors, which resolved when Ball left Zurich, a city where Dada was initially founded.[1]

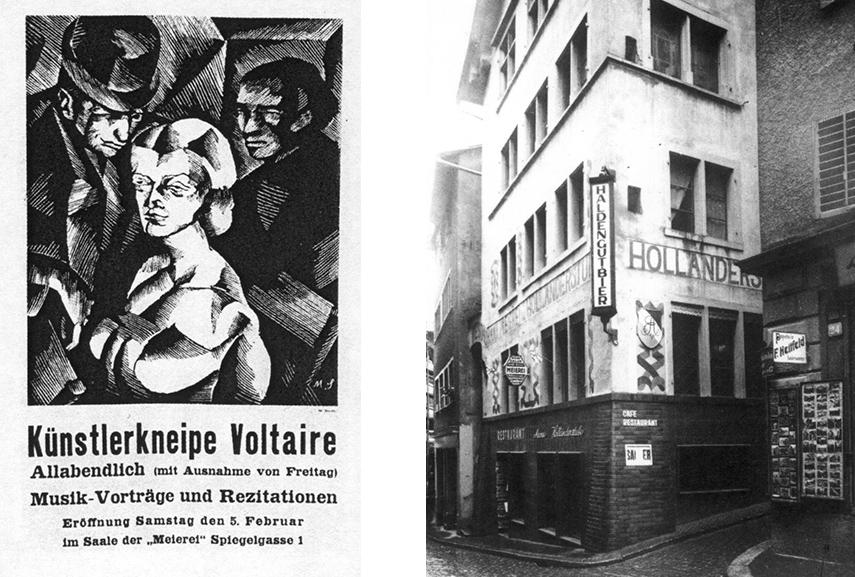

The creation of Dada came during the First World War when young creatives living at the time in neutral Switzerland decided to take their aim at the perceived ills of the modern time that led to the war, such as bourgeoisie and nationalism. Later to be known as Dadaists, these creatives looked for alternative modes of social functioning that would disengage them from the unsavory reality of the times, and which would produce a new social ordering more aligned with their desires and wishes. The founding moment for the movement came on February 5, 1916 when Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings established Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich. Other members of Dada from its initiation were Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Marcel Janco. Dada was influenced by Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, and Constructivism, and shared with other avant-garde movements the urge to change the world. Ball and Tzara soon became the leaders of the movement, but their collaboration did not managed to surpass the differences in opinion detectable in Dada manifestos they wrote.

The Apocalyptic Mind of Dada

How did these manifestos come to be? What were the mindsets that created them, or broader cultural climate surrounding and affecting their appearance and content? One element that surely influenced the authors and somehow necessitated the writing of manifestos is anti-intellectualism of the time. At the turn of the century, anarchists put deeds above ideas, and young creatves became influenced by them, including the future Dadaists. Anarchism desired to unhinge the natural energies of man form institutional constrains. The links between anarchist thought and Dada are traceable through writings and biographies of several of its members, including Hugo Ball. He was familiar with the works of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, and was reading at the time the works of well-known anarchists such as Michael Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. What Dadaists shared with anarchists is the state of mind that could be defined as apocalyptic, which anticipates “an imminent cosmic cataclysm in which God destroys the ruling powers of evil and raises the righteous to life in a messianic kingdom.”[2] Only that Anarchy and Dada would stand in the place of God. The Manifest became the instrument of Dada statement, as its proclamatory nature followed the postulates set out by the anarchists of putting deeds above ideas.[3] However, it denies reasons or motives for any present or future action, which led many to call it instead an anti-manifest, and the whole movement a non-movement. Dada manifestos in general were polemical texts that attacked reason, rational precepts, the principle of contradiction, and were often incendiary in tone.

Ball’s Manifesto - Against the Accursed Language

“Dada world war without end, dada revolution without beginning, dada, you friends and also-poets, esteemed sirs, manufacturers, and evangelists. Dada Tzara, dada Huelsenbeck, dada m’dada, dada m’dada dada mhm, dada dere dada, dada Hue, dada Tza.” - Hugo Ball, Dada Manifest[4]

Ball’s manifest from 1916 is considered a prototypic manifest of Dada. It starts with an explanation of what the word dada means in different languages. It was written before the First Dada Evening on July 14, 1916 - the evening that Dadaists described as an anti-homage to France’s Bastille Day. On that evening he performed his sound poetry. Although Dada was anti-artistic, in his text the author dangerously approaches aesthetic debate when he explains how words should be purified of “filth that clings to this accursed language”.[5] His poetic formulation expunges language from its utilitarian purpose, and word combinations turn into sonorous conjurations.

“elomen elomen lefitalominal

wolminuscaio

baumbala bunga

acycam glastula feirofim flinsi

elominuscula pluplubasch

rallalalaio”[6]

This is one of the stanzas from Ball’s poem Walken, which is probably the best illustration of where he was heading with the use of language. His manifest although created with an anti-art agenda in line with Dadaist principles, strangely sways towards artistic elaborations on the use and the meaning of language and its aesthetic potential, which resonates with the writings of Stéphane Mallarmé. However, this becomes less surprising when put in the context of anarchist thought of the time. He criticizes artistic tendency and his anti-art is actually an urge for art that will be purged of tradition, history and artistic tendencies. It is art that will turn artists inward, and become the expression of individual spirituality, or in Bakunin’s words: “art as…the return of abstraction to life.”[7]

1918 Dada Manifesto

Tzara’s Manifest - Dada Does Not Mean Anything

“Freedom: DADA DADA DADA, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE.” – Tristan Tzara, Dada Manifesto[8]

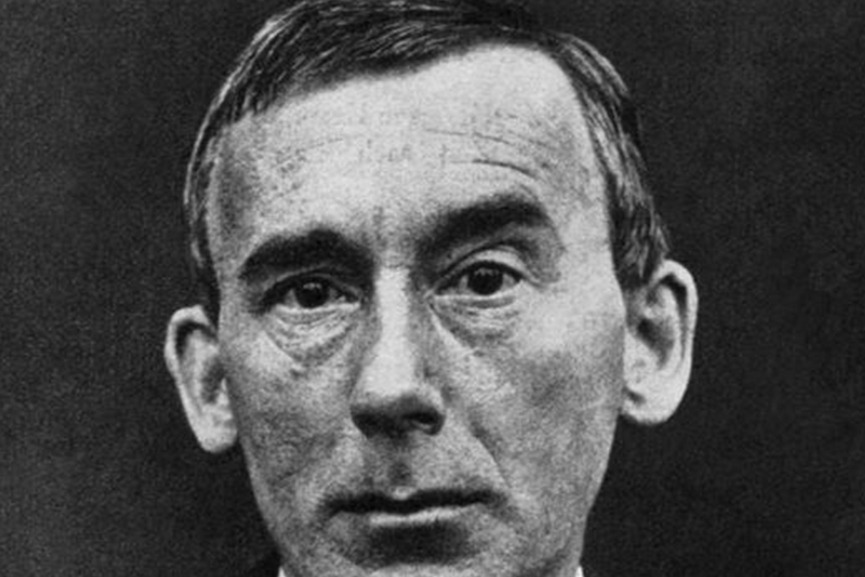

Manifeste de Monsieur Antipyrine was Tzara’s first Dada manifesto that he read on the same evening when sound poems were performed. In it he states, among other things that “Dada remains within the framework of European weaknesses, it's still shit, but from now on we want to shit in different colours so as to adorn the zoo of art with all the flags of all the consulates.”[9] He denounces war, humanity, and art. It is a foundation of his future writings and a castigation of tradition, society, and politics that have dehumanized people. The language Tzara uses reveals his anti-futurist attitudes, and the rejection of progress. Manifeste Dada from 1918 is Tzara’s second manifest that was published in Dada 3. It is described as the great gospel of Dada, where Tzara elaborates further on Dada’s postulates. He explains how in contrast to rational mind and bourgeois mentality that try to decipher and understand everything, Dada on the other hand has no meaning. He sees art as meaningless, and as a tool for self-purification. Journalists try to instill art with meaning but art in itself is “absolute in the purity of its cosmic and regulated chaos.”[10] He also calls for anti- human action, which can be today perhaps best explained through a reference to Sartre who similarly wanted to dismantle false humanism. Tzara’s call for anti-human action is not a call for action against a human but a plea for perseverance of human integrity against the stale morality and customs.

Hugo Ball versus Tristan Tzara – Anarchist and Futurist Influences

The manifestos we explained here rely heavily on the notions spread out by the anarchists who devalued tradition, social mores, and poked at morality of the modern man that is conditioned by oppressive, mechanized reality. Italian Futurism and its manifest also affected the development of Dada, and the activist and aggressive ideas of Marinetti that Tzara adopted led to a split between Ball and Tzara. While the first envisioned Dada similarly to an Expressionist cabaret, and his idea of spreading Dadaism around Europe was a pacifist one based in proselytizing through dialog, Tzara pushed for a more incisive action. He allegedly “lose sleep” over notoriety of Marinetti and replicated many of the Futurists’ modes of action, including writing manifestos and agitating for the cause around the Europe.[11] Being in disagreement with Tzara, Ball left the leadership of the movement to him, and moved out of Zürich in 1917.

Editors’ Tip: Seven Dada Manifestos and Lampisteries

Tristan Tzara—poet, literary iconoclast, and catalyst—was the founder of the Dada movement that began in Zürich during World War I. His ideas were inspired by his contempt for the bourgeois values and traditional attitudes toward art that existed at the time. For Tzara, art was both deadly serious and a game. The playfulness of Dada is evident in the manifestos collected here, both in Tzara's polemic—which often uses dadaist typography—as well as in the delightful doodles and drawings contributed by Francis Picabia. Also included are Tzara's Lampisteries, a series of articles that throw light on the various art forms contemporary to his own work.

References:

- Lista G., Sheridan S.,(1996), The Activist Model; or Avant-Garde as Italian Invention, South Central Review, Vol. 13, No.2/3, p.25.

- Definition of Apocalypse, Meriam-Webster Dictionary. merriam-webster.com [December 15, 2016]

- Anonymous, Manifestos and Movements, p. 99.

- Sterling B., (2016), Hugo Ball’s Dada Manifest, July 1916, wired.com [December 16, 2016]

- Ibid.

- Ball H., (1928), Walken, dada-companion.com [December 16, 2016]

- Bakunin M., (1871), God and the State, p. 147.

- Tzara T., (1918), Dada Manifesto, 391.org [December 16, 2016]

- Tzara T., (1916), Monsieur Antipyrine's Manifest, 391.org [December 16, 2016]

- Tzara T., (1918), Dada Manifesto.

- Lista G., Sheridan S.,(1996), The Activist Model, p.14.

Featured images: A poster made by Theo van Doesburg and Kurt Schwitters to advertise their 1923 Dada tour of Holland. Image via wsj.com. Tristan Tzara, by Man Ray, 1921. Dada collage, dada readymade.Images via Widewalls archive. All images used for illustrative purposes only.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.